Abstract

Objective:

We compared the survival of trauma patients in urban versus rural settings after the implementation of a novel rural non-trauma center alternative care model called the Model Rural Trauma Project (MRTP).

Materials and Methods:

We conducted an observational cohort study of all trauma patients brought to eight rural northern California hospitals and two southern California urban trauma centers over a one-year period (1995-1996). Trauma patients with an injury severity score (ISS) of >10 were included in the study. We used logistic regression to assess disparities in odds of survival while controlling for Trauma and Injury Severity Score (TRISS) parameters.

Results:

A total of 1,122 trauma patients met criteria for this study, with 336 (30%) from the rural setting. The urban population was more seriously injured with a higher median ISS (17 urban and 14 rural) and a lower Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) (GCS 14 urban and 15 rural). Patients in urban trauma centers were more likely to suffer penetrating trauma (25% urban versus 9% rural). After correcting for differences in patient population, the mortality associated with being treated in a rural hospital (OR 0.73; 95% CI 0.39 to 1.39) was not significantly different than an urban trauma center.

Conclusion:

This study demonstrates that rural and urban trauma patients are inherently different. The rural system utilized in this study, with low volume and high blunt trauma rates, can effectively care for its population of trauma patients with an enhanced, committed trauma system, which allows for expeditious movement of patients toward definitive care.

Keywords: Major trauma outcome study, rural trauma, urban trauma center

INTRODUCTION

Injury continues to be a leading cause of death and disability throughout the United States. However, there are significant differences between injuries that occur in rural versus urban settings. Trauma patients in rural locations are typically older, less severely injured, and more likely to die at the scene than urban patients.[1] The majority of trauma in rural settings is blunt injury with fewer penetrating injuries, while the reverse is true for urban locations.[2] Similarly, the fatal crash rate is more than twice as high in rural than urban areas, with a rural rate of approximately 2.4 deaths/100 million vehicle miles traveled.[3] Despite this, the historical focus of trauma system development has centered only on the designation of urban-based trauma centers. Few non-trauma center alternative models of care existed, and very few trauma patient outcome studies have been conducted in the rural setting. Prior to 1999, California Trauma Regulations limited rural and urban areas to one, level I, II, or III, trauma center for every 350,000 residents (or 350 major trauma patients per year) and did not include a level IV trauma center option.

In rural communities, level III trauma centers have on-call trauma surgeons and in-house trauma teams, while level IV facilities usually do not. In a retrospective review of level III trauma hospitals in Oregon, Hedges et al. identified hospital interventions that were associated with improvement in survival.[4] They noted that the administration of blood products to patients with a presenting systolic blood pressure of less than 90 mmHg, and transferring patients both with an injury severity score (ISS) greater than 20 and a systolic blood pressure of greater than 90 mmHg to a higher level of care conferred increased survival in their patient population.

The northwest corner of California is a rural region with limited trauma care resources. North Coast Emergency Medical Services (NCEMS) operates across this remote tri-county region of approximately 6,838 square miles.[5] In the mid-1980s, NCEMS identified a high rate of preventable injury death in this region. Because of the long distances between hospitals, a central trauma center was not a practical solution. Instead, the State of California Emergency Medical Services Authority supported the development of a non-trauma center rural alternative, called the Model Rural Trauma Project (MRTP).[6] The rural alternative was an attempt to improve the management of major trauma in these remote communities. The MRTP included three key elements: A warning system for the arrival of major trauma patients using trauma triage criteria, early activation of a trauma team in the emergency department (ED), and periodic systems review and modification. In a three-year retrospective study, the MRTP was found to have similar patient survival in major trauma patients when comparing to the national Major Trauma Outcome Study (MTOS) expected norms.[5]

Given the experience with the MRTP, this study was conducted to compare the survival of moderately-to-severely injured trauma patients in urban versus this rural environments using Trauma and Injury Severity Score (TRISS) methodology to control for differences not related to location. With the implementation of the rural alternative to trauma care, we hypothesized that outcomes in urban versus rural trauma care would not be substantially different.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted an observational, cohort study using a consecutive series of all trauma patients brought to eight rural, northern California study hospitals and two urban trauma centers located in Los Angeles County (Harbor-UCLA Medical Center and Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center) between 09/01/95 and 8/31/96.

Rural trauma system

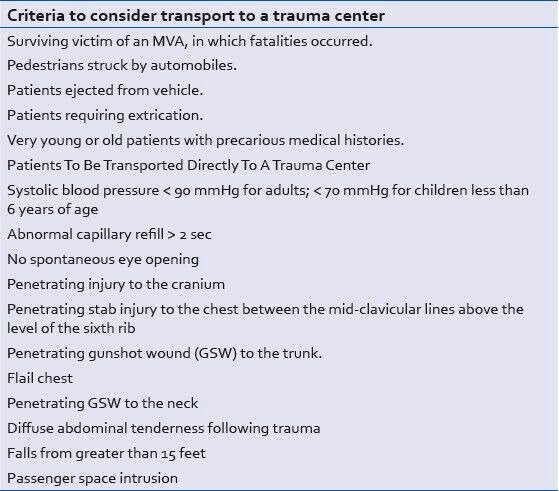

The North Coast EMS Agency (NCEMSA) served a rural region in California, which included Humboldt, Del Norte, Southern Trinity, and Lake Counties. The NCEMSA covered over 6,000 square miles with a population of 210,000 persons (approximately 23 persons per square mile). Pre-hospital providers included Emergency Medical Technician-basic (EMT-B), EMT-intermediate, and EMT-paramedics (EMT-P). Patients meeting trauma triage criteria [Table 1] were transported to the closest of eight area hospitals. EMTs contacted the hospital staff prior to arrival to relay patient information, which provided the basis for trauma team activation. Trauma team level of response at each of the receiving hospitals was divided into three levels with level III being the most resource intense, [Table 2] and level of response was decided by the emergency physician based on predefined criteria as outlined in Table 1. None of the participating hospitals within the region were designated trauma centers.

Table 1.

Rural trauma system trauma triage criteria (North Coast EMS Agency)

Table 2.

Rural trauma team levels of response to trauma activation

Urban trauma system

Harbor-UCLA and Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Centers were two of 13 level I trauma centers within a large metropolitan of Los Angeles County, CA. The Los Angeles County EMS Agency (LAEMSA) covers over 4,000 square miles, and population was estimated at 10,000,000 persons (approximately 250 persons per square mile). The Los Angeles County EMS system consisted of 72 receiving centers and 2300 EMT-Ps. Rescues were staffed by two paramedics, who transport trauma patients to one of 13 trauma centers based on Trauma Triage Criteria [Table 3]. Patients with uncontrollable hemorrhage, obstructed airway, or full arrest following trauma were transported to the closest facility. Trauma team activation occurred at the two urban hospitals with an attending trauma surgeon, anesthesiologist, and subspecialists both on-call and in-house. The study period spanned one year, from September 1, 1995 to August 31, 1996. Patients in the urban hospitals were enrolled if they met Los Angeles County trauma criteria [Table 3] and were brought via emergency medical services (EMS) personnel. Patients in the rural hospitals were enrolled if they had an ICD-9-CM discharge diagnosis of 800-959 and either required trauma team activation [Table 1] or died as a result of trauma. Only patients with an ISS ≥ 10 were included in the analysis. In the rural hospitals only, trauma patients transported to the ED by EMS or by family could be included in this study.

Table 3.

Urban trauma system trauma triage criteria

The study was approved by the institutional review boards (IRB) at the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute (LABioMed) at Harbor-UCLA and the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. All eight rural hospitals signed a memorandum of understanding with LABioMed for participation in the study.

Investigators were in the ED or were in contact with ED staff by telephone daily to ensure capture of all eligible patients. Patients were also identified through the trauma logs at the respective institutions. Records of patients who were present in the ED during the day or who had been in the ED during the previous night were reviewed, and physicians, nurses, and other health care personnel involved in patient care were contacted when documentation was not clear.

To maximize the reliability of recovered data, we used closed response data-sheets and trained data abstractors. The completeness of the patient cohort was verified daily using a separate log, which listed all patients seen in the ED. EMS, ED, in-patient, and coroner's records were subsequently retrospectively reviewed by three investigators (AJL, PJB, PDF) using standardized data sheets. Also, an informal trial period was initiated in the NCEMS region prior to actual data collection to practice data collection and determine the best methods to access charts. Inter-rater reliability for AIS scoring and neurological outcome was evaluated during this trial period on 100 patient care records. The Cerebral Performance Category (CPC) was utilized for determination of neurological outcome.[7] CPC Categories ranged from A to E with A being good overall performance (Healthy, alert, and capable of normal activities of daily life) and E being severe disability (coma or vegetative state). Patients were excluded if they did not meet the locally defined trauma criteria, were transported to the ED by other than EMS personnel (urban only), or were transferred from an outside facility. Patients brought initially to one ED who were later transferred to other facilities were included, and their data were abstracted from records at both the original receiving hospital and the transfer receiving hospital.

ISSs were determined using the 1990 revision of the Abbreviated Injury Severity Scale[8] by three individuals (AJL, PJB, PDF) formally trained by the Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine. Inter-rater reliability for ISS determination was evaluated using the Spearman rank correlation coefficient and has been previously reported.[9] To obtain follow-up information, hospital and clinic records were reviewed a minimum of six months after the patient was discharged from the initial visit.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using a commercially available statistical analysis package (SAS 9.1, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Ordinal data were summarized by medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) and were compared using the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test. Categorical data were analyzed using the chi-square or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate, and between-group measures are reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant, and no adjustments were made for multiple comparisons.

An extension of the TRISS model for predicting survival was used to adjust for differences in injury severity in comparing outcomes between the rural and urban settings. First, the SAS procedures PROC MI and PROC MIANALYZE were used to multiply impute missing data elements required for the calculation of the revised trauma score (RTS) and the TRISS predicted probability of survival. The regression coefficient obtained from the TRISS model for each subject was used to represent each subject's injury severity. We then performed multivariable logistic regression with the TRISS coefficient and the treatment site (urban versus rural) as the two independent variables and survival as the dependent variable. Importantly, the TRISS regression coefficient was considered a predictor variable, with its own logistic regression coefficient, an approach that provided greater flexibility for the model in adjusting for injury severity. In other words, we did not assume the TRISS predicted mortality estimates were quantitatively correct or calibrated in our population but, instead, only that they were a valid measure of the relative odds of survival.

RESULTS

During the defined one-year study period, a total of 2201 trauma patients were transported to the two urban hospitals; of those, 786 (36%) were excluded because they had ISS scores less than 10, and an additional 222 (10%) were excluded because of missing ISS information. In the rural setting, 339 patients were entered in the registry as having an ISS ≥ 10, though 3 (1%) did not have an ISS score recorded and were thus excluded from the study.

In total, there were 1122 trauma patients with an ISS ≥ 10 entered into the analysis, with 336 (30.0%) of them presenting to one of the rural hospitals. Overall, 322 (28.7%) were female, 232 (20.7%) were 55-years-old or older, and 899 (80.1%) suffered blunt injuries. The median age was 32.5 (IQR: 21.5 −50.5) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Patient characteristics

The urban and rural trauma populations were different in multiple baseline characteristics. The rural victims tended to be older, had a higher percentage of females, and had a predominance of Caucasians. Blunt injuries were more frequent in the rural setting. While motor vehicle accidents represented approximately 31% of the mechanisms in both populations, falls were more common in the rural setting, whereas gunshot wounds and pedestrians struck by vehicles were relatively more frequent in the urban setting [Table 4].

No rural patients were sent home from the ED, whereas a small number of urban patients were discharged home. A considerably higher percentage of urban patients were admitted to a monitored setting or taken directly to the operating room. Hospitalizations were shorter on average for rural patients, and fewer rural patients died [Table 5].

Table 5.

Patient disposition and neurological outcome

The patients in the urban group tended to have modestly lower pre-hospital systolic blood pressure, a wider range of Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) values (i.e., more patients with lower values), and a higher ISS [Table 5].

As noted above, GCS and Revised Trauma Score (RTS) values were calculated separately using pre-hospital and ED information, when available. We noted that there was a higher mortality rate among those patients for whom an ED-based RTSs could not be calculated because of missing ED information. In the urban setting, 43% of the patients who did not have complete information to calculate an ED-based RTS died as compared to the overall 16% of deaths among all urban patients. In the rural setting, 54% of those with missing ED-based RTS scores died versus 9% of all patients brought to rural EDs.

To address the missing values, the TRISS scores were calculated using multiple imputation.[10,11] The imputation included various demographic factors, mechanism of injury, individual components of the TRISS score (both pre-hospital and ED-based), transport times, resuscitation and imaging information, operative procedures performed, discharge status, ICU days, and survival. The physiologic and ISS components of the TRISS scores, after multiple imputations, are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Physiologic and ISS components of TRISS

After controlling for TRISS, the odds of survival in the rural population were not different than in the urban population, using either the pre-hospital or ED values for the TRISS calculation (Pre-hospital data: OR 0.73 (95% CI 0.41 – 1.31; ED data: OR 0.73 (95% CI 0.39-1.39).

DISCUSSION

Trauma patients in rural communities are known to have a higher rate of mortality than their peers in urban centers.[12] In a study evaluating the differences in times to trauma care, Esposito et al. found that the crude death rate in rural settings was three times that of urban areas.[12] In patients surviving long enough to reach the hospital, there is a threefold increase in risk of ED death among those injured in a region with limited access to a trauma care center, according to Gomez et al.[13] Theories to explain this discrepancy include differences in pre-hospital care, delays in transit time, prolonged discovery time, and severity of illness.[14,15]

In 1994, Karsteadt et al. examined this issue by comparing survival rates of rural trauma patients before and after implementing the MRTP.[5] They compared the actual survival rates of trauma patients to those predicted by TRISS methodology and found significant improvement in survival. Similarly, Zulick et al. examined survival at their rural level II trauma center and found that it was similar to the predictions of TRISS and comparable with care at urban level I trauma hospitals.[16] Norwood and Myers compared mortality rates at their rural-based level I trauma center in Urbana, IL with the MTOS.[17] Despite low patient volumes in their hospital, they observed a similar survival comparison to the MTOS population. Both Norwood and Zulick attributed their success to an organized trauma team with set protocols and a dedicated ED staff. Norwood noted that standardized orders and protocols were valuable as they helped maintain care standards across multiple providers. In Tulsa, OK where the city's population is 350,000, Thompson et al. examined the survival of injury patients to their level II trauma center.[18] When comparing their community hospital with predictions by MTOS, they found that outcomes were similar.

In this study, we compared the outcomes of two urban level I trauma centers to eight rural hospitals. Few studies have compared large hospital systems in this manner when evaluating trauma patient outcomes. Certain difficulties apply when comparing such a large and diverse patient cohort, such as differences in patient demographics and injury patterns in the two systems. In addition, there may be geographic and other uncontrollable factors that influence outcomes in ways not appreciated in our comparison. However, we found that overall survival was indistinguishable between rural and urban hospitals after correcting for differences in patient populations.

Our study reaffirms the assertion that rural trauma hospitals can have outcomes comparable to urban hospitals in survival, despite low patient volume. Several studies have noted that modest interventions such as set protocols for trauma, early activation of a trauma team, and standardized orders helped increase survival without the need for a formal level I trauma hospital. Our study supports this notion with a large patient cohort in rural northern California.

Limitations

There are a number of important limitations to our study. First, the date this study was first conducted (18 years earlier), and therefore, patterns of injury and models of care may have changed in the interim possibly affecting our results. Second, the ability of TRISS to correct for differences in severity of injury and other baseline characteristics and to predict mortality is controversial and has been the source of debate for quite some time.[19]

We noted that sicker patients (in terms of mortality) tended to be missing more data required to calculate the TRISS score from the ED data than was the general population. Because we used TRISS scores to adjust for difference among patients, different sources for missing data between the urban and rural groups could result in bias. To help address this concern, instead of eliminating the incomplete records of the sicker urban patients (“complete-case analysis,”) we chose to make the assumption that the data were missing at random and that we could, therefore, use multiple imputation to use the available data to characterize the missing values.[9,10] Available data, including the outcome, were included in the imputation procedure.

CONCLUSION

This study demonstrates that the overall mortality between the urban and rural trauma systems was not significantly different. A rural trauma system, with low volume and high blunt trauma rates, can effectively care for its population of trauma patients with an enhanced, committed trauma system, which allows for expeditious movement of patients toward definitive care, without hospital bypass of major trauma patients to designated trauma centers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Supported in part by grants from the State of California Emergency Medical Services Authority (Federal Block Grant Fund numbers – 4016, 4062, 1994-1995).

Footnotes

Source of Support: Supported in part by grants from the State of California Emergency Medical Services Authority (Federal Block Grant Fund numbers – 4016, 4062, 1994-1995).

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rogers FB, Shackford SR, Hoyt DB, Camp L, Osler TM, Mackersie RC, et al. Trauma deaths in a mature urban vs rural trauma system. A comparison. Arch Surg. 1997;132:376–82. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430280050007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peitzman A, Sarani B. Phase 0: Damage control resuscitation in the prehospital and emergency department settings. In: Pape HC, Peitzman A, Schwab CW, Giannoudis PV, editors. Damage Control Management in the Polytrauma Patient. 1st ed. New York: Springer; 2009. p. 103. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coben JH. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA).Contrasting rural and urban fatal crashes 1994-2003. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:574–5. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hedges JR, Adams AL, Gunnels MD. ATLS practices and survival at rural level III trauma hospitals, 1995-1999. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2002;6:299–305. doi: 10.1080/10903120290938337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karsteadt LL, Larsen CL, Farmer PD. Analysis of a rural trauma program using the TRISS methodology: A three-year retrospective study. J Trauma. 1994;36:395–400. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199403000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.State of California, Emergency Medical Services Authority: California Rural EMS Study. EMSA 392-05. 1992 Mar [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stiell IG, Nesbitt LP, Nichol G, Maloney J, Dreyer J, Beaudoin T, et al. OPALS Study Group. Comparison of the Cerebral Performance Score and the Health Utilities Index for survivors of cardiac arrest. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:241–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The abbreviated injury scale, 1990 revision. Des Plaines, IL: Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine; 1990. Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lipsky AM, Gausche-Hill M, Henneman PL, Loffredo AJ, Brueske PJ, Cryer HG, et al. Prehospital hypotension is a predictor of the need for emergent, therapeutic surgery in trauma patients with normal systolic blood pressure in the emergency department. J Trauma. 2006;61:1228–33. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000196694.52615.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haukoos JS, Newgard CD. Advanced statistics: Missing data in clinical research--part 1: An introduction and conceptual framework. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:662–8. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newgard CD, Haukoos JS. Advanced statistics: Missing data in clinical research--part 2: Multiple imputation. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:669–78. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esposito TJ, Maier RV, Rivara FP, Pilcher S, Griffith J, Lazear S, et al. The impact of variation in trauma care times: Urban versus rural. Prehosp Disaster Med. 1995;10:161–6. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00041947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomez D, Berube M, Xiong W, Ahmed N, Haas B, Schuurman N, et al. Identifying targets for potential interventions to reduce rural trauma deaths: A population-based analysis. J Trauma. 2010;69:633–9. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181b8ef81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rogers FB, Shackford SR, Osler TM, Vane DW, Davis JH. Rural trauma: The challenge for the next decade. J Trauma. 1999;47:802–21. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199910000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coben JH. Commentary: Contrasting rural and urban fatal crashes 1994-2003. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:575–7. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zulick LC, Dietz PA, Brooks K. Trauma experience of a rural hospital. Arch Surg. 1991;126:1427–30. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1991.01410350121020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norwood S, Myers MB. Outcomes following injury in a predominately rural population based trauma center. Arch Surg. 1994;29:800–5. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1994.01420320022003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson CT, Bickell WH, Siemens RA, Scara JC. Community hospital level II trauma center outcome. J Trauma. 1992;32:336–43. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199203000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gabbe BJ, Cameron PA, Wolfe R. TRISS: Does it get better than this? Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:181–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]