Abstract

Background

Little is known about the utility of plasma Aβ in clinical trials of Alzheimer’s disease.

Methods

We analyzed longitudinal plasma samples from two large multicenter clinical trials: (1) donezepil and vitamin E in mild cognitive impairment (n=405, 24 months) and (2) simvastatin in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s (n=225, 18 months).

Results

Baseline plasma Aβ was not related to cognitive or clinical progression. We observed a decrease in plasma Aβ40 and 42 among APOE-ε4 carriers relative to noncarriers in the mild cognitive impairment trial. Patients treated with simvastatin showed a significant increase in Aβ compared to placebo. We found significant storage time effects and considerable plate-to-plate variation.

Conclusions

We found no support for the utility of plasma Aβ as a prognostic factor or correlate of cognitive change. Analysis of stored specimens requires careful standardization and experimental design, but plasma Aβ may prove useful in pharmacodynamic studies of anti-amyloid drugs.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s Disease, mild cognitive impairment, MCI, plasma amyloid, biomarkers, apolipoprotein E, bioassay, luminex, innogenetics, donepezil, simvastatin

1. INTRODUCTION

Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have profoundly affected the course of AD research, drug development, and clinical practice. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and neuroimaging measures of amyloid, presumably reflecting principal pathology of AD, are among the leading biomarkers. Given the somewhat invasive nature of CSF sampling and the expense of neuroimaging, plasma Aβ would be an attractive alternative biomarker. While it is known that there is communication between the peripheral and central Aβ pools (via receptor mediated as well as passive mechanisms), the utility of plasma Aβ measurements has remained limited. Some studies have shown correlations between plasma Aβ and dementia risk and/or progression, although many of such findings have been inconsistent. Biological and methodological issues likely contribute to these limitations, thereby underlining the need for a better understanding of the biology and dynamics of plasma Aβ as well as the need for studies with longer follow-up to determine the clinical utility of measuring plasma Aβ.

As with CSF, changes in plasma Aβ may reflect changes within the brain [1–3], but may also be more affected by peripheral factors. In subjects with familial AD or Down syndrome, plasma Aβ begins to increase before dementia onset, perhaps reflecting increased Aβ production [4–9]. Investigations of plasma Aβ as a predictor of dementia in sporadic or late-onset forms of AD have had inconsistent results (reviewed in [10]). Relationships have been found with plasma Aβ40 or 42 and dementia, but the direction of these associations varies among studies [11–16]. Some studies have found an association between lower Aβ42:40 ratios and higher risk of AD [17, 18]. Sources of variability in findings from existing studies are potentially due to variability in subject age and/or with disease severity [12, 19, 20], but may also relate to study size; very few large-scale studies have been attempted. A recently published study in a cohort of N=997 non demented elderly patients found that cognitive reserve and plasma Aβ42:40 are associated, and the relationship is accentuated in those with low cognitive [21]. However the predictive value of the plasma Aβ42:40 ratio was low.

Rodent studies demonstrate that a high cholesterol diet can increase levels of Aβ, which can be reversed by 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-(HMG) CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) drug treatment [22, 23]. Simvastatin, an HMG CoA reductase inhibitor penetrates the CNS and has been shown to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and death. It was selected for use in an Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study (ADCS) randomized clinical trial to test the hypothesis that lipid lowering could reduce the clinical progression in subjects with AD who have cholesterol levels not otherwise requiring treatment. The study concluded that cholesterol levels decreased significantly in the statin group, but there was no effect on cognitive decline [24]. The effect of statin treatment on plasma Aβ was not assessed in the primary analysis, though it has been the subject of several investigations [25–28]. No studies of Aβ in plasma or CSF have found an effect of statin treatment [29] [28, 30, 31], though several reported changes in amyloid precursor protein and improvements in cognition.

We assessed the relationships among plasma Aβ and clinical progression, treatment, and APOE using banked plasma from two large ADCS clinical trials: (1) donezepil and vitamin E in mild cognitive impairment (n=405, 24 months) [32, 33] and (2) simvastatin in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s (n=225, 18 months) [24]. Our primary goal was to determine covariates that may be associated with plasma Aβ40, 42 or ratio in the setting of AD clinical trials of 18 – 24 months duration. We also investigated the value of plasma Aβ as a predictive biomarker of clinical change, or an outcome measure in pharmacodynamic studies.

2. Methods

2.1 ADCS MCI trial

The 36 month, three arm, placebo controlled ADCS MCI trial examined the effect of vitamin E or donepezil in MCI patients (clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00000173)[33]. A total of 769 patients with amnestic MCI were randomized to vitamin E, donepezil, or placebo. Complete information on inclusion, exclusion criteria and the treatment regimen has been reported [32, 33]. Serial blood samples were taken and plasma was aliquoted and banked (Appendix A).

2.2 ADCS simvastatin trial

The potential benefit of 18 months of statin treatment on cognitive decline in AD was examined by the ADCS (clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00053599). Individuals aged 50 years or older with probable AD and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) within the range 12 to 26 were included. Individuals were excluded if they had other neurological or psychiatric diagnoses that could interfere with cognitive function, were taking lipid lowering drugs, or had conditions requiring cholesterol lowering treatment as defined by the Adult Treatment Panel (ATP III) guidelines. They were also excluded if they had LDL cholesterol below 80 mg/dL or triglycerides >500 mg/dL. Complete information on inclusion, exclusion and treatment regimen has been reported [24]. As with the MCI study, blood samples were taken and plasma was banked (Appendix A).

2.4 Plasma analysis and internal standard

Plasma was assayed, quantified, and quality controlled as described in Appendices B and C. Each assay plate also included a plasma sample derived from blood drawn by venipuncture of a 56-year-old cognitively normal volunteer in a single afternoon. This internal standard provided a means for adjusting plate-to-plate variation and assessing freezer storage effects.

2.5 Statistical methods

Storage effects on the internal standard were estimated by ordinary least squares regression of Aβ concentration on the number of years since the sample was obtained from the volunteer. We examined the associations between covariates of interest and plasma Aβ at baseline using linear mixed-effects models adjusting for the internal standard [34]. The covariates of interest include age, education, gender, APOE-ε4, ADAS-Cog, ADL, MMSE, urea nitrogen, creatinine, total protein, albumin, total cholesterol, hemoglobin, and platelets. See Appendix D for details.

To estimate the correlation between change in Aβ and change specific covariates, we used a multivariate outcome linear mixed-effects model approach [35]. Typically one would estimate correlation of change by a two-step process: (1) calculate or estimate each individual’s change from baseline for each outcome, (2) calculate the usual correlation coefficients for change in each pair of outcomes. Instead we used multivariate outcome mixed-effect models to estimate in a single step the correlation of change in each pair of outcomes. The model directly estimates the correlation between random slopes for two outcomes in one step. This approach is more efficient and powerful for detecting correlations of change.

To account for the plate effects in our longitudinal models of treatment and APOE-ε4 group differences in Aβ40, Aβ42, and the log ratio of Aβ42 to Aβ40; we used linear mixed-effects models with subject-specific effects nested within plate-specific effects [34]. The models treat time as categorical and provide estimates of differences between groups at each time point. We also considered adding effect to the model for sample storage time, subject age, creatinine, hemoglobin, total protein, albumin, and platelets. We considered both the baseline level of the labs and change in the labs as potential covariates. Rather than pre-specifying which covariates should be included, we used the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) [36] to objectively select covariates. Briefly, AIC utilizes the familiar likelihood framework in combination with a penalty for model complexity with the goal of determining which covariates comprise the most predictive model.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Quality control

In the MCI trial, duplicate plasma samples were obtained from n=480 subjects at baseline, n=375 at 2 years, and n=338 subjects at 3 years. After excluding samples with CV greater than 20%, we analyzed data from n=405 subjects at baseline, n=349 at 2 years, and n=309 at 3 years. Similarly, for the simvastatin trial we obtained samples from n=242 subjects at baseline and n=206 at 1.5 years; and of these n=225 at baseline and n=190 at 1.5 years were used in the analysis. The range of storage times of the MCI samples was from 7.81 to 13.4 years across all study visits. The storage time range for samples from the simvastatin trial was 3.95 to 7.82 years.

3.2 Baseline characteristics

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the subjects that had analyzable plasma Aβ samples passing quality control versus those that did not. In the MCI trial, subjects with versus without analyzable plasma Aβ data were younger, less female, more APOE-ε4 positive, and had higher levels of Creatinine. In the simvastatin trial, subjects with analyzable plasma Aβ data had lower levels of Creatinine compared with those that did not have analyzable plasma Aβ data.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics.

Mean (standard deviation) and counts (percentages) of baseline characteristics among those with plasma Aβ samples that passed quality controls versus not. P-values are from Wilcoxon rank-sum or Fisher’s exact tests.

| MCI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | Without Aβ (N=364) | With Aβ (N=405) | Combined (N=769) | P-value |

|

|

|||||

| Age [yrs] | 769 | 73.70 (7.42) | 72.23 (7.10) | 72.93 (7.28) | 0.008 |

| Gender : Female | 769 | 182 (50%) | 170 (42%) | 352 (46%) | 0.030 |

| Education [yrs] | 769 | 14.57 (3.12) | 14.70 (3.05) | 14.64 (3.08) | 0.423 |

| APOE-ε4 alleles: | 769 | 0.007 | |||

| 0 | 146 (40%) | 199 (49%) | 345 (45%) | ||

| 1 | 186 (51%) | 161 (40%) | 347 (45%) | ||

| 2 | 32 (9%) | 45 (11%) | 77 (10%) | ||

| ADAS11 | 765 | 11.33 (4.31) | 11.23 (4.44) | 11.28 (4.38) | 0.636 |

| ADL | 768 | 46.00 (4.94) | 45.91 (4.63) | 45.95 (4.77) | 0.455 |

| MMSE | 769 | 27.13 (1.89) | 27.39 (1.81) | 27.27 (1.85) | 0.054 |

| Urea Nitrogen | 689 | 16.90 (4.11) | 17.66 (5.16) | 17.34 (4.76) | 0.290 |

| Creatinine | 689 | 0.869 (0.190) | 0.915 (0.227) | 0.896 (0.213) | 0.010 |

| Total Protein | 689 | 7.082 (0.431) | 7.053 (0.449) | 7.065 (0.441) | 0.240 |

| Albumin | 689 | 4.161 (0.233) | 4.175 (0.246) | 4.169 (0.240) | 0.466 |

| Total Cholesterol | 688 | 215.2 (37.2) | 213.1 (37.1) | 214.0 (37.1) | 0.480 |

| Hemoglobin | 686 | 13.95 (1.18) | 14.11 (1.25) | 14.04 (1.22) | 0.126 |

| Platelets | 686 | 233.1 (54.6) | 224.9 (52.8) | 228.4 (53.7) | 0.068 |

| AD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | Without Aβ (N=181) | With Aβ (N=225) | Combined (N=406) | P-value |

|

|

|||||

| Age [yrs] | 406 | 74.88 (9.44) | 74.35 (9.18) | 74.58 (9.29) | 0.533 |

| Gender : Female | 406 | 102 (56%) | 139 (62%) | 241 (59%) | 0.309 |

| Education [yrs] | 406 | 14.40 (3.38) | 14.14 (3.08) | 14.25 (3.21) | 0.290 |

| APOE-ε4 alleles: | 358 | 0.626 | |||

| 0 | 64 (39%) | 86 (44%) | 150 (42%) | ||

| 1 | 78 (48%) | 84 (43%) | 162 (45%) | ||

| 2 | 21 (13%) | 25 (13%) | 46 (13%) | ||

| ADAS11 | 403 | 24.35 (9.82) | 24.07 (10.28) | 24.19 (10.07) | 0.669 |

| ADL | 406 | 67.7 (10.0) | 68.0 (10.3) | 67.9 (10.2) | 0.491 |

| MMSE | 406 | 20.32 (4.72) | 20.37 (4.69) | 20.35 (4.70) | 0.900 |

| Urea Nitrogen | 405 | 17.27 (4.87) | 17.18 (4.96) | 17.22 (4.91) | 0.779 |

| Creatinine | 405 | 0.904 (0.202) | 0.860 (0.208) | 0.879 (0.206) | 0.010 |

| Total Protein | 405 | 7.171 (0.437) | 7.141 (0.477) | 7.154 (0.459) | 0.267 |

| Albumin | 405 | 4.122 (0.290) | 4.174 (0.309) | 4.151 (0.301) | 0.076 |

| Total Cholesterol | 405 | 211.8 (30.1) | 212.1 (30.8) | 212.0 (30.5) | 0.888 |

| Hemoglobin | 401 | 13.99 (1.23) | 14.01 (1.24) | 14.00 (1.24) | 0.975 |

| Platelets | 398 | 246.5 (74.7) | 249.1 (57.2) | 247.9 (65.4) | 0.233 |

3.2 Storage effects and plate-to-plate variation of biological standard

Figure 1 depicts the storage effect that we observed from the biological standard that was aliquoted on each plate. Storage time of the biological standard ranged from 0 to 1.8 years. We found that estimated Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations of the biological standard declined significantly over time (−14.42 pg/ml Aβ40 per storage year, SE=1.32, p<0.001; −1.893 pg/ml Aβ42 per storage year, SE=0.616, p=0.003). The standard deviations of the residuals from these models, σ=6.9 pg/ml Aβ40 and σ=3.2 pg/ml Aβ42, provide measures of the plate-to-plate variability, controlling for storage. Figure 1 also demonstrates a wide range of estimated concentrations, even within a short time frame. In the samples assayed within 40 days of venipuncture, for instance, the range is nearly 21.6 pg/ml for Aβ40, and about 7.58 pg/ml for Aβ42. The inter-plate CV, adjusted for storage effect, was 15.1% for Aβ40 and 24.5% for Aβ42, while the median intra-plate CV was 6.0% for Aβ40 and 8.3% for Aβ42.

Figure 1. Storage Effects.

Each plate included an aliquot from the same healthy control sample. We observed a significant linear effect of storage time on the estimated concentration of this sample. Estimated storage time plots are from an ordinary least squares regression. Shaded regions indicate 95% confidence bounds.

3.3 Baseline associations with plasma Aβ40, Aβ42, and log ratio of Aβ42 to Aβ40

Table 2 summarizes the associations among covariates and Aβ40 and Aβ42. Aβ40 was positively associated with Aβ42 in both trials (2.223 pg/ml Aβ40 per pg/ml Aβ42 SE=0.118, p<0.001 in the MCI trial; and 4.606 pg/ml Aβ40 per pg/ml Aβ42 SE=0.335, p<0.001 in the simvastatin trial). In the MCI trial, we found Aβ40 and Aβ42 were positively associated with age (1.041 pg/ml Aβ40 per year of age, SE=0.324, p=0.001; and 0.163 pg/ml Aβ42 per year of age, SE=0.083, p=0.047); urea nitrogen (0.8697 pg/ml Aβ40 per mg/dl urea nitrogen, SE=0.432, p=0.045; and 0.3515 pg/ml Aβ42 per mg/dl urea nitrogen, SE=0.113, p=0.002); and creatinine (25.712 pg/ml Aβ40 per mg/dl creatinine, SE=9.656, p=0.008; and 10.890 pg/ml Aβ42 per mg/dl creatinine, SE=2.531, p<0.001). In the simvastatin trial, Aβ40 was positively associated with hemoglobin (3.949 pg/ml Aβ40 per g/dl hemoglobin, SE=1.954, p=0.044); and Aβ42 was positively associated with ADAS-Cog (0.0714 pg/ml Aβ42 per ADAS-Cog point, SE=0.0334, p=0.033). The log ratio of Aβ42 to Aβ40 was significantly associated with creatinine (0.16 per mg/dl, SE= 0.07, p=0.026) and platelets (−7.4×10−4 per 1000/μl, SE=−3.1×10−4, p=0.016) in the MCI trial.

Table 2. Baseline Associations.

Associations between the indicated variables at baseline as estimated by linear mixed effect model with plasma Aβ40 or Aβ42 as the outcome. Each estimate is on a different scale. For example, in MCI, Aβ40 increased an estimated 1.04 pg/ml per year of age.

| Variable | Baseline Associations with Aβ40 (pg/ml) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCI | AD | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Estimate | SE | p-value | Estimate | SE | p-value | |

| Aβ42 (pg/ml) | 2.22 | 0.12 | <0.001*** | 4.61 | 0.34 | <0.001*** |

| Age (years) | 1.04 | 0.32 | 0.001** | 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.988 |

| Education (years) | 0.18 | 0.78 | 0.819 | −0.45 | 0.80 | 0.572 |

| Gender: | ||||||

| Male | 160.83 | 5.75 | 0.268 | 130.83 | 5.13 | 0.849 |

| Female | 165.99 | 4.65 | 130.11 | 8.44 | ||

| ApoE-ε4: | ||||||

| 0 | 159.15 | 6.02 | 0.301 | 128.61 | 8.40 | 0.625 |

| 1 | 166.71 | 4.88 | 123.03 | 5.76 | ||

| 2 | 162.17 | 7.61 | 125.63 | 8.74 | ||

| ADAS-Cog | 0.44 | 0.52 | 0.394 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 0.077† |

| ADL | −0.50 | 0.49 | 0.310 | −0.16 | 0.23 | 0.500 |

| MMSE | −1.49 | 1.26 | 0.239 | −0.46 | 0.52 | 0.379 |

| Urea nitrogen (mg/dl) | 0.87 | 0.43 | 0.045* | −0.45 | 0.49 | 0.365 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 25.71 | 9.66 | 0.008** | 12.36 | 11.80 | 0.296 |

| Total protein (g/dl) | −3.60 | 5.07 | 0.478 | −2.08 | 5.01 | 0.679 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 2.31 | 9.01 | 0.797 | 7.06 | 7.81 | 0.367 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.580 | −0.06 | 0.08 | 0.473 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | −1.29 | 1.79 | 0.472 | 3.95 | 1.95 | 0.044* |

| Platelets (1000/μl) | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.051† | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.386 |

| Variable | Baseline Associations with Aβ42 (pg/ml) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCI | AD | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Estimate | SE | p-value | Estimate | SE | p-value | |

| Age (years) | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.047* | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.663 |

| Education (years) | 0.33 | 0.19 | 0.081† | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.570 |

| Gender: | ||||||

| Male | 39.43 | 1.29 | 0.761 | 19.09 | 0.73 | 0.955 |

| Female | 39.07 | 1.18 | 19.05 | 0.72 | ||

| ApoE-ε4: | ||||||

| 0 | 40.10 | 1.37 | 0.419 | 18.81 | 0.80 | 0.406 |

| 1 | 38.70 | 1.24 | 19.63 | 0.83 | ||

| 2 | 38.25 | 1.89 | 18.07 | 1.26 | ||

| ADAS-Cog | −0.13 | 0.13 | 0.311 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.033* |

| ADL | −0.03 | 0.13 | 0.827 | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.285 |

| MMSE | 0.17 | 0.32 | 0.591 | −0.11 | 0.07 | 0.135 |

| Urea nitrogen (mg/dl) | 0.35 | 0.11 | 0.002** | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.883 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 10.89 | 2.53 | <0.001*** | 2.75 | 1.72 | 0.110 |

| Total protein (g/dl) | −1.51 | 1.30 | 0.244 | −0.94 | 0.74 | 0.201 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 1.37 | 2.33 | 0.555 | 0.39 | 1.12 | 0.731 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.759 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.760 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | −0.07 | 0.47 | 0.884 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.429 |

| Platelets (1000/μl) | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.622 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.384 |

| Variable | Baseline Associations with log ratio of Aβ42 to Aβ40 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCI | AD | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Estimate | SE | p-value | Estimate | SE | p-value | |

| Age (years) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.912 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.878 |

| Education (years) | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.115 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.576 |

| Gender: | ||||||

| Male | −1.42 | 0.04 | 0.131 | −1.89 | 0.05 | 0.751 |

| Female | −1.47 | 0.05 | −1.90 | 0.06 | ||

| ApoE-ε4: | ||||||

| 0 | −1.40 | 0.05 | 0.056† | −1.90 | 0.06 | 0.181 |

| 1 | −1.48 | 0.05 | −1.84 | 0.06 | ||

| 2 | −1.45 | 0.06 | −1.93 | 0.08 | ||

| ADAS-Cog | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.363 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.877 |

| ADL | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.889 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.591 |

| MMSE | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.205 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.638 |

| Urea nitrogen (mg/dl) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.226 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.430 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.026* | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.280 |

| Total protein (g/dl) | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.077† | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.278 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.857 | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0.787 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.912 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.292 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.765 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.254 |

| Platelets (1000/μl) | −7.4×10−4 | −3.1×10−4 | 0.016* | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.944 |

3.4 Correlates of change

Table 3 summarizes the correlates of change in Aβ40 and Aβ42. In MCI, change in Aβ40 was positively correlated with change in Aβ42 (ρ=0.842, 95% CI 0.779 to 0.912) and change in Aβ40 was positively correlated with change in platelets (ρ=0.170, 95% CI 0.036 to 0.308). Similarly, in the simvastatin trial, change in Aβ40 was correlated with change in Aβ42 (ρ=0.713, 95% CI 0.606 to 0.804). In the MCI trial, change in log ratio of Aβ42 to Aβ40 was correlated with ADAS-Cog (ρ=0.145, 95% CI 0.019 to 0.274), ADL (ρ=−0.178, 95% CI −0.309 to −0.055), and urea nitrogen (ρ=−0.168, 95% CI −0.305 to −0.039). Note that higher scores on ADAS-Cog indicate worse cognition and higher scores on the ADL indicate better daily function.

Table 3. Correlations of Change.

Correlations between change in AB40 and change in each other indicated variable as estimated by multivariate outcome mixed-effect models. We estimated the lower and upper bounds of the 95% confidence intervals by 1,000 simulations. Correlations that are significantly different form zero are indicated in bold.

| Variable | MCI | AD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corr. (95% CI) | Corr. (95% CI) | ||

| Aβ40 | Aβ42 | 0.842 (0.779,0.912) | 0.713 (0.606,0.804) |

| ADAS-Cog | −0.038 (−0.152,0.075) | −0.016 (−0.206,0.179) | |

| ADL | −0.072 (−0.181,0.044) | −0.043 (−0.239,0.144) | |

| MMSE | −0.071 (−0.197,0.051) | −0.015 (−0.204,0.176) | |

| Urea nitrogen | −0.024 (−0.161,0.106) | - | |

| Creatinine | 0.034 (−0.094,0.159) | - | |

| Total protein | 0.015 (−0.112,0.131) | - | |

| Albumin | 0.010 (−0.125,0.128) | - | |

| Total Cholesterol | 0.039 (−0.090,0.175) | −0.001 (−0.199,0.199) | |

| Hemoglobin | −0.014 (−0.149,0.125) | - | |

| Platelets | 0.170 (0.036,0.308) | - | |

|

| |||

| Aβ42 | ADAS-Cog | 0.044 (−0.062,0.162) | 0.033 (−0.147,0.216) |

| ADL | −0.100 (−0.218,0.006) | −0.040 (−0.219,0.141) | |

| MMSE | −0.115 (−0.251,0.002) | −0.081 (−0.278,0.114) | |

| Urea nitrogen | 0.053 (−0.077,0.186) | - | |

| Creatinine | 0.032 (−0.108,0.156) | - | |

| Total protein | −0.035 (−0.167,0.085) | - | |

| Albumin | −0.065 (−0.194,0.071) | - | |

| Total Cholesterol | −0.021 (−0.148,0.100) | −0.127 (−0.303,0.050) | |

| Hemoglobin | −0.079 (−0.205,0.044) | - | |

| Platelets | 0.038 (−0.095,0.161) | - | |

|

| |||

| log ratio of Aβ42 to Aβ40 | ADAS-Cog | 0.145 (0.019, 0.274) | −0.089 (−0.263, 0.120) |

| ADL | −0.178 (−0.309,−0.055) | 0.185 (−0.008, 0.351) | |

| MMSE | 0.062 (−0.073, 0.205) | −0.048 (−0.239, 0.143) | |

| Urea nitrogen | −0.168 (−0.305,−0.039) | ||

| Creatinine | 0.009 (−0.133, 0.152) | ||

| Total protein | −0.060 (−0.193, 0.074) | ||

| Albumin | −0.098 (−0.228, 0.043) | ||

| Total Cholesterol | −0.018 (−0.151, 0.118) | 0.161 (−0.021, 0.360) | |

| Hemoglobin | −0.087 (−0.222, 0.031) | ||

| Platelets | −0.085 (−0.212, 0.052) | ||

3.5 APOE-ε4 group differences in Aβ change

The top of Figure of 2 shows the modeled change in Aβ40 and Aβ42 by the number of APOE-ε4 alleles. In MCI we see significantly greater change from baseline in Aβ40 and Aβ42 at three years among APOE-ε4 non-carriers compared to carriers. Change in Aβ40 at three years was greater in those with no alleles compared to those with one allele (41.7 pg/ml, SE=6.69, p<0.001) or two alleles (55.7 pg/ml, SE=9.54, p<0.001). Change in log ratio of Aβ42 to Aβ40 at year 3 in MCI was greater for those with one versus no allele (0.12, SE=0.04, p=0.019). The AIC selected model of Aβ40 included age; baseline creatinine; and baseline and change in hemoglobin, albumin and platelets. The AIC selected model of Aβ42 included age; and change in creatinine, hemoglobin, and platelets. The AIC selected model of log ratio of Aβ42 to Aβ40 included baseline creatinine, total protein, hemoglobin, and platelets; and change in creatinine, total protein, albumin, and platelets. No significant differences between APOE-ε4 groups were observed in the simvastatin trial.

3.6 Treatment group differences in Aβ change

The bottom of Figure 2 shows the modeled change in plasma Aβ species by treatment group. In the MCI trial, Aβ40 and Aβ42 increased more at 3 years in the placebo group compared to donepezil (33.9 pg/ml Aβ40, SE=7.68, p<0.001; 12.63 pg/ml Aβ42, SE=2.04, p<0.001) or vitamin E (39.3 pg/ml Aβ40, SE=7.53, p<0.001; 7.81 pg/ml Aβ42, SE=2.01, p<0.001). Change in log ratio of Aβ42 to Aβ40 was greater at 3 years with vitamin E compared to placebo (0.14, SE=0.049, p=0.012), but no difference was found with donepezil. In the simvastatin trial, both Aβ species increased more at 18 months in the simvastatin group compared to placebo (21.3 pg/ml Aβ40, SE=6.55, p=0.001; 4.34 pg/ml Aβ42, SE=0.923, p<0.001), but the difference in change of log ratio of Aβ42 to Aβ40 was not significant (−0.10, SE=0.062, p=0.010).

Figure 2. Linear mixed effects model estimates of change in plasma Aβ by treatment and APOE-4.

Change in plasma Aβ was modeled by number of APOE-ε4 alleles (top) and treatment group (bottom). Covariates in these models were selected by AIC. Specifically models of Aβ40 included age; baseline creatinine; and baseline and change in hemoglobin, albumin and platelets. The models of Aβ42 included age; and change in creatinine, hemoglobin, and platelets. Models of Aβ42 to Aβ40 (log) ratios included baseline creatinine, total protein, hemoglobin, and platelets; and change in creatinine, total protein, albumin, and platelets.

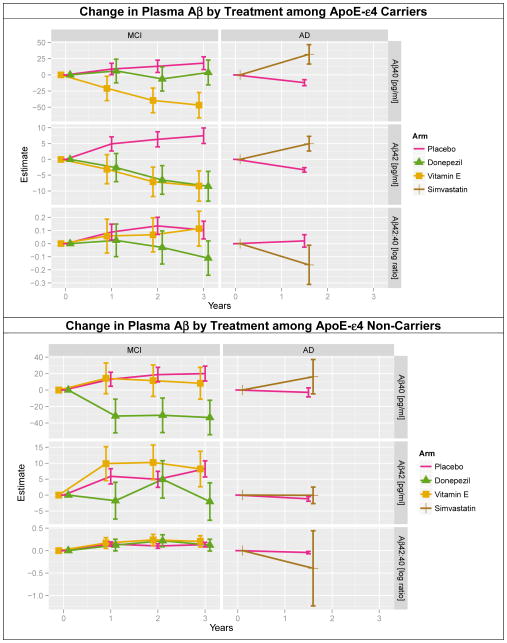

3.7 Treatment group differences in Aβ change within APOE-ε4 subgroups

Figure 3 shows the modeled change in plasma Aβ species by treatment group within each APOE-ε4 group. For APOE-ε4 carriers in the MCI trial, both Aβ species increase significantly more at 3 years in the placebo group compared to vitamin E (64.8 pg/ml Aβ40, SE=10.8, p<0.001; 15.89 pg/ml Aβ42, SE=2.65, p<0.001), and Aβ42 increased more at 3 years in the placebo group compared to donepezil (15.96 pg/ml Aβ42, SE=2.68, p<0.001). The log ratio of Aβ42 to Aβ40 decreased more with donepezil compared to placebo (−0.21, SE=0.074, p=0.009). For APOE-ε4 carriers in the simvastatin trial, both Aβ species increased significantly at 18 months in the simvastatin group compared to placebo (43.8 pg/ml Aβ40, SE=8.99, p=0.001; 8.28 pg/ml Aβ42, SE=1.37, p<0.001); and the log ratio decreased more with simvastatin (−0.18, SE=0.091, p=0.044). For APOE-ε4 non-carriers in the MCI trial, both Aβ species increased more at 3 years in the placebo group compared to donepezil (53.4 pg/ml Aβ40, SE=11.3, p<0.001; 10.28 pg/ml Aβ42, SE=3.17, p=0.002); and there was no difference in change in log ratio of Aβ42 to Aβ40. There were no significant differences in Aβ change between simvastatin and placebo among the APOE-ε4 non-carriers

Figure 3. Linear mixed effects model estimates of change in plasma Aβ by treatment within APOE-4 subgroups.

Change in plasma Aβ was modeled by treatment among APOE-ε4 carriers (top) by treatment among APOE-ε4 non-carriers (bottom). Covariates in these models were selected by AIC. Specifically models of Aβ40 included age; baseline creatinine; and baseline and change in hemoglobin, albumin and platelets. The models of Aβ42 included age; and change in creatinine, hemoglobin, and platelets. Models of Aβ42 to Aβ40 (log) ratios included age; and baseline and change in creatinine, total protein, hemoglobin, albumin, and platelets.

4. DISCUSSION

In comparison to CSF, plasma Aβ has been an inconsistent predictor of dementia in sporadic or late-onset forms of AD. Associations have been found between plasma Aβ40 and 42 and dementia, but the direction of these associations vary among studies [11–15, 37]. More consistency has been found in the ratio of plasma Aβ42:40, with non-demented patients usually having higher risk of AD with lower Aβ42:40 ratios [17, 18]. In terms of predicting whether patients with MCI will convert to AD, no consistent change in plasma Aβ or ratio has been found [12, 13, 37]. However, studies demonstrate that age-related changes (increases) in plasma Aβ and reduced Aβ40:42 ratio are primarily restricted to MCI patients or individuals with worsening cognitive status [37].

Variability in these findings is potentially due to sample variability in subject age and/or with disease severity [12, 20], but may also relate to study size. Very few large-scale studies have been attempted. A recently published study in a large cohort of elderly patients identified an association between low cognitive reserve and plasma Aβ42:40, which accentuated the relationship between low plasma Aβ42:40 and greater cognitive decline in non-demented participants [21]. As mentioned above, plasma Aβ has been reported to begin increasing before dementia onset in subjects with familial AD or Down Syndrome, perhaps reflecting increased Aβ production [5–7]. The same has not been found in sporadic or late-onset forms of AD. Although relationships have been found with plasma Aβ40 or 42 and dementia, the direction of these associations is variable. In particular, a recent Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) study of plasma Aβ42 in normal, mildly impaired and mildly demented cohorts, found that plasma Aβ measurements were not useful in distinguishing among the cohorts, and showed minimal association with disease progression [37]. Although discouraging, this study found a significant association between plasma Aβ42 and brain amyloid, as indicated by CSF Aβ42. The ADNI study also found a correlation of plasma Aβ42 and other biomarkers of Aβ pathology [37]. As opposed to studies examining levels of peptide, reports on ratio of plasma Aβ42:40, have had more consistent results, with lower Aβ42:40 ratios predicting higher risk of AD [17, 18]. Furthermore, a large cohort study of elderly patients found that low cognitive reserve and plasma Aβ42:40, which accentuated the relationship between low plasma Aβ42:40 and greater cognitive decline in non-demented participants [21].

We found that APOE-ε4 carriers demonstrated significant reduction of Aβ compared to non-carriers in our MCI cohort, while this relationship was not observed in the AD statin trial. A possible explanation is that APOE-ε4 group differences in plasma Aβ are only apparent in milder populations, and populations with more severe impairment are more homogeneous across APOE-ε4 groups.

Despite the fact that both studies found no effect on their primary outcomes, we did observed significant, though inconsistent, treatment effects on Aβ in both trials. Active groups in the MCI trial demonstrated decreased Aβ and the statin group demonstrated increased Aβ. Although the original statin trial itself was negative, our plasma biomarker data suggests further study of the effect of statins on Aβ is warranted. It is surprising that presumed symptomatic agents, donepezil and vitamin E, appeared to affect plasma Aβ in AD. All of our treatment-related findings should be interpreted with caution until confirmed in studies with parallel CSF or amyloid imaging.

We observed greater inter-assay CVs than some previous reports, but our intra-assay CVs were within the range of many prior reports (e.g. [37]). Collection, preparation and handling of plasma samples can all influence variability. The inter-assay CVs we observed could have been elevated due to preparation, handling, or storage of the samples or the analytic kits. Recent data also suggest that technical precision may also be involved. Using a robotized method for specific steps allowed for a large improvement in consistency over results reported in the literature, and several significant relationships between plasma and CSF biomarkers have been found using this method [38]. Although the authors concluded that these associations are not strong enough to support use of plasma Aβ as a diagnostic screening test, these data and those observed in immunotherapy trials (e.g. [39], for review [40]) suggests that plasma Aβ42 may be useful as a pharmacodynamic marker.

Due to plate-to-plate variability seen with the Innogenetics platform, we find that inclusion of one or more internal standard controls and sound experimental design and analysis are crucial. In particular, we recommend that samples be randomized so that key features (e.g. treatment assignment, APOE-ε4, gender) are well balanced on each plate. Good experimental design can help ensure that plate effects are not confounded with other effects of interest.

The statistical models (Appendix D) included fixed-effect covariates for mean-centered biological standard assayed on each plate. This model allows for plate-level covariate adjustment, similar to familiar adjustments for subject-level covariates. A more naïve approach subtracts the biological control from each observation before submitting to the final regression analysis. In a perfectly balanced design, point estimates from the covariate adjustment approach would be identical to the naïve approach, but naïve standard error estimates would be incorrect because they do not account for variability in the biological control. We also include subject- and plate-specific random effects to account for the correlation structure of these repeated measures, plate-clustered data.

We also recommend that samples from an individual be aliquoted to the same plate. This helps ensure that plate effects are not confounded with longitudinal effects. Unfortunately, this means that storage effects are confounded with longitudinal effects; however we have found that storage effects are small relative to plate-to-plate variation. In this setting, estimates of group differences are valid under the assumption that storage effects are similar in the groups being compared.

When considering our results and those from other groups, an important factor to consider is blood processing time. The ADCS choses to process blood samples for plasma stores centrally to reduce variations in pre-analytic handling. This requires that whole blood samples are shipped in ambient temperature gel packs overnight and processed at approximately 24hrs postdraw. Our decision to maintain this strategy is supported by our internal studies (Rissman and Aisen, unpublished observations) and investigations by other groups that have tested stability of Aβ in plasma. Stability experiments assessing the effect of time-to-processing demonstrate that mean (SD) Aβ1–40 decreased from 267 (46) pg/ml at time 0 to 190 (41) pg/ml at 24 hours and 143 (33) pg/ml at 48 hours; or an average decrease of about 2.6 pg/ml/hr [41]. Similarly, Aβ1–42 decreased from 29 (4) pg/ml at time 0 to 2 (4) pg/ml at 24 hours and 19 (3) pg/ml at 48 hours; or an average decrease of about 0.2 pg/ml/hr. Their conclusion was that processing should be done within 24 h and peptide ratios should be created to minimize artificial results. Other groups conducted similar experiments and found plasma concentrations of Aβ (particularly Aβ-42) appeared stable in whole blood processed as long as 24 hours after collection [42]. While comparisons of absolute Aβ across studies is problematic, group comparisons within a study in the present manuscript should be less so. This is because samples from different groups of interest have been handled similarly within a particular study, and samples have been randomized to plates to prevent confounding of plate and group effects.

With improvements of assay conditions (e.g., with increasing sensitivity and reproducibility, and standardization of specimen handling to minimize interactions with other blood constituents and collection materials); and sound experimental design and analysis to control confounding factors such as batch effects, age and renal function; plasma Aβ may become a useful biomarker of brain amyloidosis. This, in turn, could greatly facilitate the development and clinical application of disease-modifying therapies for AD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH/NIA AG010483, AG032755, and 1KL2RR031978 awarded by the University of California, San Diego Clinical and Translation Research Institute (1UL1RR031980). The authors thank Louise Lindberg and Kathleen Lao (ADCS, UCSD) for technical support.

Appendix A. Sample Collection

Informed consent was obtained from patients and their caregivers for all procedures, in accordance with local regulatory procedures in the context of each clinical trial to be described below. Consent to banking for AD research was obtained for all samples. Whole blood samples from the two clinical were drawn at sites in the US and Canada. Blood collection was performed with a 21g needle and drawn into lavender top EDTA tubes. Samples were shipped overnight at room temperature and processed at a central laboratory. Average time between blood collection and processing was 24hrs. Plasma preparation was accomplished by centrifugation of whole blood at 1800g (3000 rpm, Eppendorf 5810R centrifuge with an A-4-81 rotor) for 10 minutes. Plasma was immediately removed after centrifugation, separated into 500ul aliquots into 1.5ml Eppendorf sterile polypropylene microtubes and stored at −80 degrees until use.

Appendix B. Plasma Aβ multiplex bioassays

Banked plasma was assessed for Aβ40 and 42 using Innogenetics Plasma Abeta Forms kits (1–40 and 1–42), according to the manufacturer instructions. Briefly, beads were placed on a washed filter plate and incubated while shaking with antibody conjugate and undiluted plasma samples overnight for 14–18 hours at 4°C. All samples were assayed in duplicate. Pre-aliquoted standards and controls came with the kit and plasma samples and were run in duplicate. The next day, the plates were washed and a detection conjugate was added and incubated while shaking at room temperature for one hour. The plate was then washed again and a reading solution added and allowed to incubate while shaking for 2–3 minutes. Plates were read on a BioRad Bioplex 200. Readings flagged as suspect based on percent aggregated beads > 30% were excluded.

Appendix C. Calibration, quantification, and quality control

Quantification of luminescent bioassays requires standard curves that map luminescence values to concentrations. We derive standard curves by assaying samples of known concentration. The Innogenetics platform provides six standards containing synthetic Aβ standard samples of known concentration, and one sample with no Aβ. These standards were assayed in duplicate on each assay plate, and modeled with a four parameter logistic model to estimate standard curves as recommend by the FDA [51]. Models allowed non-constant power of the mean error variance if warranted, which provides more efficient estimation of the regression parameters [52]. If the four parameter logistic model with non-constant variance failed to converge, a four parameter logistic model with constant variance was applied, followed by a three parameter logistic model with non-constant variance as necessary. One plate from the simvastatin study only had duplicate readings from only 3 non-zero standards, and therefore a quadratic model with non-constant variance was used. The lower limit of quantification was determined by the lowest concentration at which the coefficient of variation (CV) was less than 20%. Plasma from each individual was analyzed on the same plate so that subject effects were nested within plate effects. Duplicate samples with CV exceeding 20% and samples with a missing reading were excluded from further analysis. Although re-running of samples with >20% CVs may have aided in increasing sample number, this was not possible. To mitigate plate-to-plate variability, plates were purchased in bulk and run consecutively. In addition, our internal plasma standard (described in methods) was aliquoted in duplicate to each plate to measure and control for plate effects in all assays.

Appendix D. Statistical Analysis

To estimate the association at baseline between Aβ and covariates of interest, x, we fit mixed-effect models of the form:

| (1) |

Here Aβ0ijk is the baseline concentration Aβ40 or Aβ42 (or the log ratio of Aβ42 to Aβ40) for subject i, duplicate reading j =1 or 2, from plate k; the γ’s are fixed effects; α0i are subject-specific random intercepts; α1k are plate-specific random intercepts; and εij are residuals. We assume the α’s and ε’s are drawn from Gaussian distributions. The parameter of interest is γ1, which is an estimate of how much Aβ changes per unit change in the other covariate of interest. We used the Aβ concentrations from the healthy control sample aliquoted to each plate to help adjust for plate effects. This was accomplished by including a fixed effect, denoted γ2 in (1), for the mean-centered biological standard reading for plate k, denoted “Aβbiok” in (1). When modeling the log ratio of Aβ42 to Aβ40, we included a covariate for both biological standard readings. Rather than modeling the mean of duplicate Aβ assays, we chose to include both in our mixed-effect model. This approach allows the analysis to be more robust to outliers and to utilize information about the assay variation that is otherwise lost. A similar model was fitted for Aβ40, Aβ42, and the log ratio of Aβ42 to Aβ40.

To estimate group effects over time, the base model of longitudinal Aβ in each treatment group was of the form:

| (2) |

Here Aβijk(t) is the Aβ40 or Aβ42 reading (or the log ratio of Aβ42 to Aβ40) for subject i, duplicate reading j, on plate k, at time t years; the γ’s are fixed effects; 1{tj=x} is 1 if tj=x and 0 otherwise; the α’s are random effects, and εij are residuals similar to model (1). We again adjust for the mean-centered plasma biological standard on each plate, Aβbiok, and we adjust for both standards when modeling the log ratio of Aβ42 to Aβ40.

The statistical software R version 3.0 [56] was used for all analyses. Calibration and quantification of plasma Aβ was performed using the calibFit package [57], linear mixed-effects models were fit with nlme [58], and graphical displays were produced with ggplot2 [59]. AIC model selection was accomplished via forward and backward search starting with the model with all covariates included. The significance level was set at α=0.05 and no corrections were made for multiple comparisons.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have no conflict of interests relevant to blood biomarker discovery research.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mayeux R, et al. Plasma amyloid beta-peptide 1–42 and incipient Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1999;46(3):412–6. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199909)46:3<412::aid-ana19>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehta PD, et al. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid levels of amyloid beta proteins 1–40 and 1–42 in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2000;57(1):100–5. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehta PD, et al. Amyloid beta protein 1–40 and 1–42 levels in matched cerebrospinal fluid and plasma from patients with Alzheimer disease. Neurosci Lett. 2001;304(1–2):102–6. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01754-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehta PD, et al. Increased plasma amyloid beta protein 1–42 levels in Down syndrome. Neurosci Lett. 1998;241(1):13–6. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00966-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheuner D, et al. Secreted amyloid beta-protein similar to that in the senile plaques of Alzheimer’s disease is increased in vivo by the presenilin 1 and 2 and APP mutations linked to familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med. 1996;2(8):864–70. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tokuda T, et al. Plasma levels of amyloid beta proteins Abeta1–40 and Abeta1–42(43) are elevated in Down’s syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1997;41(2):271–3. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ertekin-Taner N, et al. Plasma amyloid beta protein is elevated in late-onset Alzheimer disease families. Neurology. 2008;70(8):596–606. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000278386.00035.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schupf N, et al. Elevated plasma amyloid beta-peptide 1–42 and onset of dementia in adults with Down syndrome. Neurosci Lett. 2001;301(3):199–203. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01657-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehta PD, et al. Plasma amyloid beta protein 1–42 levels are increased in old Down Syndrome but not in young Down Syndrome. Neurosci Lett. 2003;342(3):155–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00275-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rissman RA, et al. Longitudinal plasma amyloid beta as a biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm. 2012;119(7):843–50. doi: 10.1007/s00702-012-0772-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayeux R, et al. Plasma A[beta]40 and A[beta]42 and Alzheimer’s disease: relation to age, mortality, and risk. Neurology. 2003;61(9):1185–90. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000091890.32140.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukumoto H, et al. Age but not diagnosis is the main predictor of plasma amyloid beta-protein levels. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(7):958–64. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.7.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopez OL, et al. Plasma amyloid levels and the risk of AD in normal subjects in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Neurology. 2008;70(19):1664–71. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000306696.82017.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schupf N, et al. Peripheral Abeta subspecies as risk biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(37):14052–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805902105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blasko I, et al. Conversion from cognitive health to mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: prediction by plasma amyloid beta 42, medial temporal lobe atrophy and homocysteine. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hampel H, et al. Biological markers of amyloid beta-related mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Neurol. 2010;223(2):334–46. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graff-Radford NR, et al. Association of low plasma Abeta42/Abeta40 ratios with increased imminent risk for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(3):354–62. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.3.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okereke OI, et al. Ten-year change in plasma amyloid beta levels and late-life cognitive decline. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(10):1247–53. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsubara E, et al. Lipoprotein-free amyloidogenic peptides in plasma are elevated in patients with sporadic Alzheimer’s disease and Down’s syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1999;45(4):537–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giedraitis V, et al. The normal equilibrium between CSF and plasma amyloid beta levels is disrupted in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2007;427(3):127–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yaffe K, et al. Association of plasma beta-amyloid level and cognitive reserve with subsequent cognitive decline. JAMA. 2011;305(3):261–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Refolo LM, et al. Hypercholesterolemia accelerates the Alzheimer’s amyloid pathology in a transgenic mouse model. Neurobiol Dis. 2000;7(4):321–31. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fassbender K, et al. Simvastatin strongly reduces levels of Alzheimer’s disease beta -amyloid peptides Abeta 42 and Abeta 40 in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(10):5856–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081620098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sano M, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of simvastatin to treat Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2011;77(6):556–63. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318228bf11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishii K, et al. Pravastatin at 10 mg/day does not decrease plasma levels of either amyloid-beta (Abeta) 40 or Abeta 42 in humans. Neurosci Lett. 2003;350(3):161–4. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00895-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoglund K, et al. Plasma levels of beta-amyloid(1–40), beta-amyloid(1–42), and total beta-amyloid remain unaffected in adult patients with hypercholesterolemia after treatment with statins. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(3):333–7. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.3.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blasko I, et al. Plasma amyloid beta protein 42 in non-demented persons aged 75 years: effects of concomitant medication and medial temporal lobe atrophy. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26(8):1135–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Serrano-Pozo A, et al. Effects of simvastatin on cholesterol metabolism and Alzheimer disease biomarkers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010;24(3):220–6. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181d61fea. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sjogren M, et al. Treatment with simvastatin in patients with Alzheimer’s disease lowers both alpha- and beta-cleaved amyloid precursor protein. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2003;16(1):25–30. doi: 10.1159/000069989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riekse RG, et al. Effect of statins on Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers in cerebrospinal fluid. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;10(4):399–406. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-10408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carlsson CM, et al. Effects of simvastatin on cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers and cognition in middle-aged adults at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;13(2):187–97. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-13209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grundman M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment can be distinguished from Alzheimer disease and normal aging for clinical trials. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(1):59–66. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petersen RC, et al. Vitamin E and donepezil for the treatment of mild cognitive impairment. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(23):2379–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laird NM, Ware JH. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1982;38(4):963–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beckett LA, Tancredi DJ, Wilson RS. Multivariate longitudinal models for complex change processes. Stat Med. 2004;23(2):231–9. doi: 10.1002/sim.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akiake H. Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. Proc Second Int’l Symp on Information Theory; 1973; Akademiai, Kiado, Budapest. pp. 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toledo JB, et al. Factors affecting Abeta plasma levels and their utility as biomarkers in ADNI. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;122(4):401–13. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0861-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Figurski MJ, et al. Improved protocol for measurement of plasma Amyloid-β in longitudinal evaluation of ADNI patients. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.01.001. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salloway S, et al. Two phase 3 trials of bapineuzumab in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(4):322–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winblad B, et al. Active immunotherapy options for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2014;6(1):7. doi: 10.1186/alzrt237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bibl M, et al. Stability of amyloid-beta peptides in plasma and serum. Electrophoresis. 2012;33(3):445–50. doi: 10.1002/elps.201100455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okereke OI, et al. Performance characteristics of plasma amyloid-beta 40 and 42 assays. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;16(2):277–85. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-0948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.