Abstract

Background

This study was undertaken to determine how well two Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) dimensions (irritable and headstrong/hurtful) assessed in childhood predict late adolescent psychopathology and the degree to which these outcomes can be attributed to genetic influences shared with ODD dimensions.

Methods

Psychopathology was assessed via diagnostic interviews of 1225 twin pairs at ages 11 and 17.

Results

Consistent with hypotheses, the irritable dimension uniquely predicted overall internalizing problems, whereas the headstrong/hurtful dimension uniquely predicted substance use disorder symptoms. Both dimensions were predictive of antisocial behavior, and overall externalizing problems. The expected relationships between the irritable dimension and specific internalizing disorders were not found. Twin modeling showed the irritable and headstrong/hurtful dimensions were related to late adolescent psychopathology symptoms through common genetic influences.

Conclusions

Symptoms of ODD in childhood pose a significant risk for various mental health outcomes in late adolescence. Further, common genetic influences underlie the covariance between irritable symptoms in childhood and overall internalizing problems in late adolescence, whereas headstrong/hurtful symptoms share genetic influences with substance use disorder symptoms. Antisocial behavior and overall externalizing share common genetic influences with both the irritable and headstrong/hurtful dimensions.

Keywords: Oppositionality, symptom dimensions, genetic, environmental, longitudinal

Introduction

The estimated lifetime prevalence rate of Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) is 1–15% Boylan, Vaillancourt, Boyle, & Szatmari, 2007; Maughan, Rowe, Messer, Goodman, & Meltzer, 2004; Nock, Kazdin, Hiripi, & Kessler, 2007) and as high as 65% in clinical samples (Boylan et al., 2007), making it one of the most common childhood disorders. Although it was previously conceptualized as a developmental antecedent to Conduct Disorder (CD; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1980; Rowe, Maughan, Pickles, Costello, & Angold, 2002), recent studies have shown ODD is often a precursor to various other forms of psychopathology including anxiety (Rowe, Costello, Angold, Copeland, & Maughan, 2010), depression (Burke, Loeber, Lahey, & Rathouz, 2005; Copeland, Shanahan, Costello, & Angold, 2009), and substance use (Nock et al., 2007; Ghosh, Malhotra, & Basu, 2014). This has begun to transform views of ODD from a ‘throw away’ diagnosis to one that may hold promise in identifying risk for later psychopathology. As such, researchers have aimed to distinguish dimensions of ODD that show distinct longitudinal relationships with other disorders. The ODD dimensions identified have not been entirely consistent across studies, but each of the proposed dimensional models has one affective component and one or two behavioral components (Burke, Hipwell, & Loeber, 2010; Rowe et al., 2010; Stringaris & Goodman, 2009a). Despite an increase in examination of ODD dimensions over recent years, research on the prospective associations between ODD dimensions in childhood and specific psychopathology in late adolescence remains mixed, and little is known about what causes those associations. The present study aimed to address these critical gaps in the literature.

Research has shown that the affective dimensions of ODD (e.g., irritable) are predictive of internalizing problems such as depression and anxiety (Burke et al., 2010; Burke, 2012; Hipwell et al., 2011; Rowe et al., 2010; Whelan, Stringaris, Maughan, & Barker, 2013), whereas the behavioral dimensions (e.g., headstrong, hurtful) are generally predictive of externalizing problems such as ADHD (Stringaris & Goodman, 2009b), conduct problems (Leadbeater & Homel, 2015; Stringaris & Goodman, 2009b), substance use (Rowe et al., 2010), and callousness (Whelan et al., 2013). However, many longitudinal studies only followed participants for two to five years, and have focused on later childhood or early adolescent outcomes. Despite the fact that late adolescence is an important developmental period when the prevalence of many disorders peaks (Merikangas et al., 2010), this time period is generally understudied (Schulenberg, Sameroff, & Cicchetti, 2004). The only studies examining outcomes in late adolescence to early adulthood have shown that the headstrong/hurtful dimension is predictive of adult conduct problems (Leadbeater & Homel, 2015) and criminal convictions (Aebi, Plattner, Metzke, Bessler, & Steinhausen, 2013), and the irritability dimension is predictive of depression (Burke, 2012). The first aim of the current study is to fill in gaps in this literature by examining a wider range of outcomes during late adolescence. The relationships between two ODD symptom dimensions (irritable and headstrong/hurtful; Rowe et al., 2010) in childhood at age 11, and psychopathology assessed via diagnostic interviews at age 17 were examined. Most prior studies used broadband scales of internalizing (Stringaris & Goodman, 2009b) or combined several disorders into a single category/dimension (Rowe et al., 2010; Lavigne, Gouze, Bryant, & Hopkins, 2014), leaving open the question of whether ODD dimensions relate to specific disorders or only to overall levels of problems. Therefore, in addition to examining specific disorders separately, disorders were also combined into overall internalizing and externalizing scores to examine how the ODD dimensions related to specific disorders as well as the broader spectrums, consistent with the approach of several prior studies.

The current study also aimed to examine the extent to which genetic influences underlie the relationships between ODD dimensions and later psychopathology. Because monozygotic (MZ) twins share 100% of their genes, dizygotic (DZ) twins share roughly 50% of their segregating genes, and all twins reared together share aspects of their environment, twin designs can provide estimates of the additive genetic, shared environmental, and nonshared environmental influences on a disorder or set of traits. Additive genetic influences refer to the sum of effects across multiple alleles which are inherited from one’s parents. Shared environmental influences are those aspects of the environment shared by both members of a twin pair that make them more similar (e.g., socioeconomic status, neighborhood). Nonshared environmental influences are those aspects of the environment unique to each twin, and therefore serve to make twins less alike (e.g., unique friendships and experiences). Estimates of nonshared environmental influences also include measurement error.

Only one study thus far has examined the genetic overlap between ODD symptom dimensions and psychopathology (Stringaris, Zavos, Leibenluft, Maughan, & Ely, 2012). Stringaris et al. (2012) found the cross-sectional genetic correlation between the irritable dimension and depression was significantly higher than the correlation between the headstrong/hurtful dimension and depression, whereas the genetic correlation between the headstrong/hurtful dimension and delinquency was significantly higher than the correlation between the irritable dimension and delinquency. Results examining two year longitudinal relationships showed the same pattern but did not reach significance (Stringaris et al., 2012). Others examining the irritability dimension as assessed by the Achenbach measures (Achenbach, 1991; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2003) showed this dimension in childhood shared genetic influences with anxiety/depression in adolescence (Savage et al., 2015), and that irritability showed genetic stability from childhood through late adolescence (Roberson-Nay et al., 2015). Krieger et al. (2013) examined familial links by assessing parental history of mental disorders. They found the irritable dimension was related with a family history of depression and suicidality, whereas the headstrong dimension was related to a family history of ADHD symptoms. These results provide some evidence for differential genetic relationships between ODD symptom dimensions and psychopathology. The second aim of the current study was to expand upon these findings by examining the shared genetic underpinnings of the ODD symptom dimensions at age 11 and psychopathology in late adolescence. Given previous findings (Kreiger et al, 2013; Savage et al., 2015; Stringaris et al., 2012), it was hypothesized that the affective dimension would have common genetic influences with each internalizing disorder and the overall internalizing score, and the behavioral dimension would have common genetic influences with each externalizing disorder and the overall externalizing score.

Method

Participants

This investigation used data from the Minnesota Twin Family Study (MTFS), a longitudinal study of same-sex twins. Minnesota state birth records were used to identify families of male twins (born 1972–1982) and female twins (born 1975–1985) and contact information was obtained through public databases. Families were excluded if they lived further than a day’s drive to the research site, if either twin had a mental or physical handicap, or if twins were adopted. This study includes the participants in the 11-year-old male and female cohorts. Additionally, an Enrichment Sample (ES) was recruited to include twins who were screened for disruptive behavior (Keyes, Malone, Elkins, Legrand, McGue, & Iacono, 2009). Twins in the ES include male and female same-sex twin pairs (born 1988–1994) who were also roughly 11-years-old at the time of intake. The combined intake sample included 2510 individuals (395 MZ male pairs, 220 DZ male pairs, 391 MZ female pairs, and 249 DZ female pairs) with a mean age of 11.78. The sample was 93% White, reflecting the ethnic composition of Minnesota during the years the twins were recruited.

Procedures

Detailed information regarding the MTFS research design and procedures is provided elsewhere (Iacono, Carlson, Taylor, Elkins, & McGue, 1999; Iacono & McGue, 2002). Prior to each assessment, informed consent/assent was obtained from all participants. The follow-up assessments included in the present study were conducted at age 17 (N=2230; 89% retention rate). Participants received monetary compensation for their participation. The MTFS follows the guidelines of, and is overseen by, the Institutional Review Board at the University of Minnesota.

Measures

Zygosity

Zygosity of the twins was determined using parent-report on a zygosity questionnaire, physical similarity of twins as rated by MFTS staff, and anthropometry measures. When these sources of information did not agree, DNA tests were used.

Diagnostic interview

Diagnostic data were obtained through structured clinical interviews; reliability across all disorders was moderate to high, kappas ≥ .62. Reliability of ODD diagnosis for 11-year-olds was .76. Children were assessed for ODD (and other disorders) using the revised Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (DICA-R; Welner, Reich, Herjanic, Jung, & Amado, 1987). Care-givers were interviewed about their children’s symptoms with the parent version of the DICA-R. For ODD at age 11, parent- and child-report were combined using a ‘best estimate’ approach (Angold & Costello, 1996; De Los Reyes et al., 2015). That is, a symptom was considered present if either the parent or child endorsed it. When the twins returned for their follow-up assessment, they were assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R or DSM-IV. Disorders assessed included major depression (MDD), specific phobia (SPP), social anxiety (SOP), panic disorder (PD), and adult antisocial behavior (AAB). Additionally, alcohol use disorder (AUD) and cannabis use disorder (CUD) symptoms were assessed using the Substance Abuse Module of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; Robins et al., 1988). It should be noted that MDD, SOP, SPP, and PD all required a ‘gateway’ symptom to be endorsed before remaining symptoms were assessed. This approach to diagnosis is efficient as endorsement of symptoms of a disorder beyond the gateway are deemed unlikely (e.g., recognizing that a fear is excessive/unreasonable cannot logically be endorsed if the gateway symptom regarding the existence of an extreme fear is not first endorsed). However, this approach may have resulted in reduced variability in symptom endorsement (e.g., suicidal ideation/attempts may be endorsed in the absence of depressed mood/anhedonia although one could argue such an endorsement would not belong in a symptom count of MDD). Also, AAB included all symptoms of antisocial personality disorder, but did not include the presence of CD in childhood. The substance use disorders (AUD and CUD) included symptoms of both abuse and dependence. At intake, interviews were lifetime assessments (‘have you ever experienced…’) whereas the follow-up assessment asked about the past three years.

Data analysis

Analyses were conducted using MPlus 7.0 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2015). Sum score variables were created for two ODD dimensions: irritable (loses temper, touchy/annoyed, angry/resentful) and headstrong/hurtful (argues, defies, annoys others, blames others, spiteful/vindictive). Psychopathology sum scores were also created by summing symptoms of each disorder, as well as combining MDD, SOP, SPP, and PD to create an internalizing sum score, and AUD, CUD and AAB to create an externalizing sum score. Sum score variables were then transformed using an inverse transformation to address skew. Relationships between ODD dimensions at age 11 and psychopathology at follow-up were examined using a series of path models. Each path model included both the irritable dimension and the headstrong/hurtful dimension as predictors, and a separate model was run for each outcome (i.e., follow-up psychopathology) variable. Maximum likelihood estimation was used to account for missing data (Allison, 2003; Enders, 2010; Graham, 2009). The underlying genetic and environmental influences of the ODD dimensions and psychopathology in late adolescence were then examined using independent pathway models. The first set of biometric factors estimated in this model reflect the genetic and environmental influences common to the two variables in the model (e.g., headstrong/hurtful and AUD), whereas the remaining sets of biometric factors represent the influences that are unique to each variable, after accounting for the first set of biometric factors.

Results

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th edition (DSM-5) criteria for ODD was met by 9.5% of the sample, which is representative of the prevalence in the population (APA, 2013; Boylan et al., 2007). Preliminary tests showed no significant differences between irritable (Mann-Whitney U = 295203, z = −1.62, p = .11) and headstrong/hurtful (Mann-Whitney U = 298524, z = −1.20, p = .23) scores between participants who were present, and those who had missing data for the follow-up assessment. The irritable and headstrong/hurtful dimensions were correlated at r = .45 (p < .001).

Results from the series of path models of ODD irritable and headstrong/hurtful dimensions predicting later psychopathology are presented in Table 1. Note that a Bonferroni correction was used to account for multiple comparisons such that a value of p < .0028 (.05/18) was required for significance. Although the irritable dimension (controlling for the headstrong/hurtful dimension) showed evidence of weak association with age 17 internalizing disorders, it was not a significant predictor of any of them, contrary to predictions. However, the irritable dimension did significantly predict the overall internalizing score. Given these results, only the overall internalizing score was retained in subsequent analyses.

Table 1.

Standardized Path Estimates (and p-values) of ODD Dimensions at age 11 Predicting Psychopathology at age 17.

| MDD | SOP | SPP | PD | INT | AUD | CUD | AAB | EXT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irritable | .065 (.013) |

.062 (.014) |

.055 (.027) |

.042 (.115) |

.082 (.002) |

.046 (.088) |

.053 (.046) |

.101 (<.001) |

.085 (.001) |

| Headstrong/Hurtful | .038 (.119) |

.007 (.799) |

−.025 (.314) |

−.002 (.936) |

.018 (.477) |

.127 (<.001) |

.107 (<.001) |

.184 (<.001) |

.180 (<.001) |

Note. Standardized path estimates represent the unique relationship between the ODD dimension and the psychopathology variable, controlling for the other ODD dimension.

MDD = Major Depressive Disorder; SOP = Social Phobia; SPP = Specific Phobia; PD = Panic Disorder; INT = Internalizing sum score; AUD = Alcohol Use Disorder; CUD = Cannabis Use Disorder; AAB = Adult Antisocial Behavior; EXT = Externalizing sum score.

Path estimates significant after Bonferroni correction are presented in bold

Consistent with predictions, the headstrong/hurtful dimension (controlling for the irritable dimension) was a significant predictor of AUD, CUD, and AAB, as well as the overall externalizing score. While not hypothesized, unique significant relationships between the irritable dimension and AAB and the overall externalizing score were also evident.

Prior to running twin models to follow up on the significant results from the path models described above, the twin correlations among ODD dimensions and psychopathology for MZ and DZ twins were examined (Table 2). The correlations were indicative of genetic influence, as they were consistently higher among MZ twins. However, MZ correlations were less than twice the magnitude of DZ correlations in some cases, suggesting shared environmental influences. The irritable dimension and AUD showed evidence of potential non-additive (i.e., interactive or due to combinations of alleles) effects, as the MZ correlations were more than twice the DZ correlation. Further, nonshared environmental influences (and measurement error) were indicated, given MZ correlations less than 1.00.

Table 2.

Twin Correlations among MZ and DZ Twins (and p-values)

| Variable | MZ | DZ |

|---|---|---|

| Irritable | .53 (<.001) | .21 (<.001) |

| Headstrong/Hurtful | .67 (<.001) | .46 (<.001) |

| INT | .31 (<.001) | .16 (.003) |

| AUD | .45 (<.001) | .21 (<.001) |

| CUD | .64 (<.001) | .38 (<.001) |

| AAB | .58 (<.001) | .31 (<.001) |

| EXT | .58 (<.001) | .36 (<.001) |

Note. INT = Internalizing sum score; AUD = Alcohol Use Disorder; CUD = Cannabis Use Disorder; AAB = Adult Antisocial Behavior; EXT = Externalizing sum score.

Preliminary univariate analyses of ODD dimensions showed significant genetic (a2 = .41; 95% CI [.23–.59]), shared environmental (c2 = .26; 95% CI [.10–.42]) and nonshared environmental (e2 = .33; 95% CI [.29–.38]) influences on the headstrong/hurtful dimension. Given that the twin correlations (in Table 2) suggested possible non-additive genetic effects (D) on the irritable dimension, an ACE model was compared to an ADE model and an AE only model. Results showed the ADE model (BIC = 277.43) fit better than the ACE model (BIC = 280.05); however, the additive (.27; 95% CI [.00–.54]) and non-additive genetic (.27; 95% CI [.00–.57]) effects were both nonsignificant. The AE model had the lowest BIC (272.91), was the most parsimonious, and was thus accepted as the best fitting model. The AE model showed significant genetic (a2 = .54; 95% CI [.48–.59]) and nonshared environmental (e2 = .46; 95% CI [.41–.52]) influences on the irritable dimension. Results from a correlated factors model showed that the irritable and headstrong/hurtful dimensions had a moderate to high genetic correlation (.63; 95% CI [.47–.80]), and a small but significant nonshared environmental correlation (.24; 95% CI [.15–.32]).

Independent pathway models were used to examine the shared genetic and environmental influences underlying the significant relationships (see Table 1) between ODD dimensions at age 11 and psychopathology at follow-up. Although the irritable and headstrong/hurtful dimensions shared genetic and nonshared environmental influences, to focus and simplify the remaining results, only the dimension(s) that showed a significant unique association to later psychopathology was/were examined in subsequent behavioral genetic analyses.

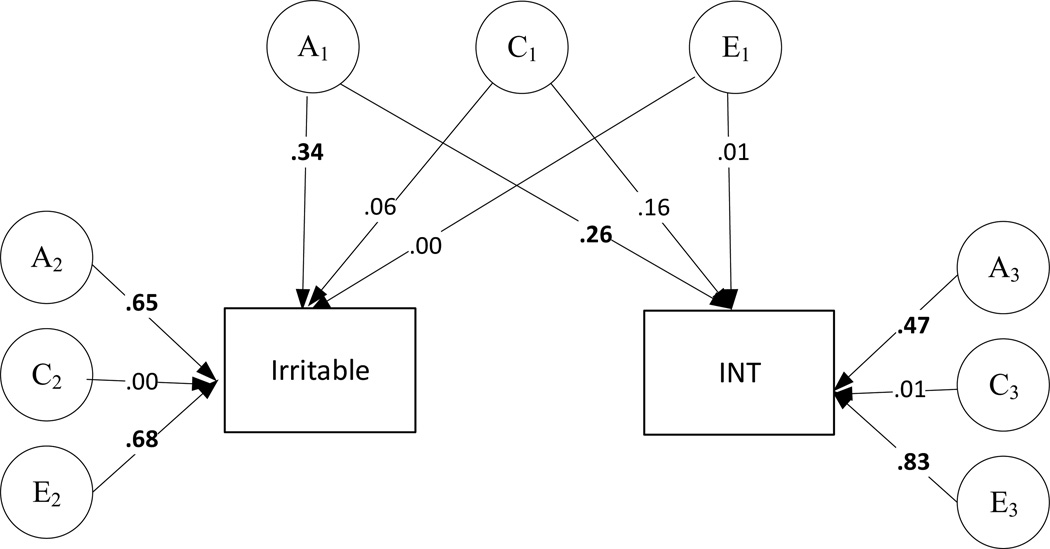

The bivariate relationship between the irritable dimension and the overall internalizing score was examined first (Figure 1). The first set of biometric factors estimated (A1, C1, and E1) were of primary interest because they represent the general genetic and environmental influences that contribute to the covariance among the irritable and internalizing scores. In support of our hypothesis, the pathways from the general genetic factor (A1) were significant (95% confidence intervals did not include 0), suggesting common genetic effects underlying the irritable dimension and overall internalizing. The common shared (C1) and nonshared environmental influences (E1) were nonsignificant. The remaining sets of biometric factors represent the genetic and environmental influences unique to the irritable dimension (A2, C2, and E2) and those unique to the internalizing score (A3, C3, and E3) beyond the variance accounted for by the general biometric factors (A1, C1, and E1). The pathways from the genetic factors (A2 and A3) and the nonshared environment factors (E2 and E3) were significant, suggesting genetic and nonshared environmental influences unique to the irritable dimension and to the internalizing score.

Figure 1.

Results from an independent pathway model of the irritable dimension and the overall internalizing sum score at follow-up. A = additive genetic influence; C = shared environmental influence; E = nonshared environmental influence; INT = internalizing sum score. Significant (95% confidence interval does not include 0) standardized parameter estimates are presented in bold.

Next, the bivariate relationships between the headstrong/hurtful dimension and substance use disorders were examined. Results showed the headstrong/hurtful dimension shared genetic influences with AUD and CUD (pathways from A1 were significant in both models; Figure 2). No other significant shared influences between the headstrong/hurtful dimension and later substance use disorders were found. Although the pathway from C1 to the headstrong/hurtful dimension was significant in the AUD model, the pathway from C1 to AUD did not reach significance, suggesting nonsignificant common shared environmental influences.

Figure 2.

Results from two independent pathway models of the headstrong/hurtful dimension and substance use psychopathology at follow-up. A = additive genetic influence; C = shared environmental influence; E = nonshared environmental influence; AUD = Alcohol Use Disorder; CUD = Cannabis Use Disorder. Significant (95% confidence interval does not include 0) standardized parameter estimates are presented in bold.

a results of AUD model.

b results of CUD model.

Although the relationships between the irritable dimension and externalizing psychopathology were not hypothesized, the results (Table 1) suggested both the irritable and headstrong/hurtful dimensions each uniquely contributed to the prediction of AAB and the overall externalizing score. As such, rather than examining bivariate relationships using independent pathway models, trivariate Cholesky models were fit. The first set of biometric factors estimated in a Cholesky model (A1, C1, and E1) represent the genetic and environmental influences specific to the first variable in the model, and those shared with the other variables in the model. The second set of biometric factors (A2, C2, and E2) represent the genetic and environmental influences specific to the second variable in the model, and those shared with the third variable in the model, after accounting for A1, C1, and E1. The third set of biometric factors (A3, C3, and E3) represent the genetic and environmental influences unique to the third variable in the model, beyond the variance accounted for by all the prior biometric factors. As shown in Figure 3, irritable, headstrong/hurtful, and AAB had common genetic influences (all paths from A1 were significant). The paths from C1 and E1 to AAB were not significant, suggesting no significant common shared environmental or nonshared environmental influences. After accounting for relationships with the irritable dimension, the headstrong/hurtful dimension did not share unique etiological influences with AAB. A similar pattern of results was also found for overall externalizing (Figure 3). Further, genetic correlations between AAB and irritable (rA = .33; 95% CI [.22–.48] and AAB and headstrong/hurtful (rA = .30; 95% CI [.07–.49]) were similar in magnitude, as were the genetic correlations between overall externalizing and irritable (rA = .35; 95% CI [.17–.59] and overall externalizing and headstrong/hurtful (rA = .36; [95% CI [.11–.65]). It should be noted that ACE models were run because the headstrong/hurtful dimension had significant shared environmental influences; however, these results should be interpreted with caution given that an AE model provided the best fit for the irritable dimension.

Figure 3.

Results from two Cholesky models of the irritable and headstrong/hurtful dimensions with adult antisocial behavior and overall externalizing sum score at follow-up. A = additive genetic influence; C = shared environmental influence; E = nonshared environmental influence; AAB = adult antisocial behavior; EXT = externalizing sum score. Significant (95% confidence interval does not include 0) standardized parameter estimates are presented in bold.

a results of AAB model.

b results of EXT model.

Discussion

The current study expanded upon the growing literature about the predictive nature of childhood ODD dimensions. To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive study addressing this topic thus far. It is the first study to include several internalizing and externalizing disorders assessed via clinical interviews, to follow a same-age cohort for a six year period into late adolescence, and to examine genetic and environmental influences contributing to these long-term relationships. The findings from this study have implications for the importance of early identification of psychopathology in childhood, as well as its developmental course, and provide further credence for the emerging attention on ODD as a useful diagnostic category.

Consistent with hypotheses, the headstrong/hurtful dimension at age 11 was uniquely predictive of substance use disorder symptoms (specifically alcohol and cannabis), antisocial behavior, and overall externalizing problems six years later at age 17. Taken together with the findings of others (Aebi et al., 2013; Leadbeater & Homel, 2015; Rowe et al., 2010), these results suggest that the headstrong/hurtful dimension has lasting predictive power and may provide an early sign for the development of externalizing psychopathology in late adolescence and early adulthood.

The irritable dimension was found to be a unique predictor for the overall internalizing score as expected. Contrary to hypotheses, we did not find significant unique relationships between the irritable dimension and later specific internalizing disorders. It should be noted that much of the work linking the irritability dimension to later internalizing problems did not include the diagnostic assessment of various disorders, but rather included broadband scales of internalizing (Stringaris & Goodman, 2009b), collapsed several disorders into a single category/dimension (Lavigne et al., 2014; Rowe et al., 2010), or assessed only depression (Burke, 2012). Therefore, it is unclear whether the irritable dimension is related to specific anxiety disorders, or just broadband traits generally associated with internalizing.

Although unexpected, results showed the irritable dimension to be a significant unique predictor of antisocial behavior and overall externalizing. While this relationship was smaller in magnitude than the predictive relationship of the headstrong/hurtful dimension, these results suggest that the irritable dimension is not specifically predictive of only later internalizing problems. These results are consistent with others who have found the affective component of ODD to be concurrently and longitudinally predictive of conduct problems (Burke et al., 2010; Stringaris & Goodman, 2009a). Further, the current study examined AAB (rather than the more frequently studied CD), which includes the symptom of irritability/aggressiveness, as indicated by physical fights. It may be that the link between the irritable dimension of ODD and antisocial behaviors is driven by emotionally reactive behavior triggered by anger (Stringaris & Goodman, 2009a).

The correlation between the irritable dimension and headstrong/hurtful dimension in this study (r = .45) was due mostly to genetic influences, and to a lesser extent, nonshared environmental influences. The magnitude of this relationship suggests these are moderately correlated but meaningfully separable dimensions, and is comparable to the correlations found in other studies (r = .48 – .91; Burke et al., 2014; Ezpeleta, Granero, de la Osa, Penelo, & Domenech, 2012; Krieger et al., 2013; Rowe et al., 2010; Stringaris & Goodman, 2009a, 2009b). The fact that the magnitude was on the low end of the range may be due to the use of diagnostic interviews rather than questionnaires, or due to the use of multiple informants rather than a single informant. The use of multiple informants at age 11 (combined child- and parent-report), an age when many children are still developing their capacity for psychological self-insight, is a strength of the current study and speaks to the reproducibility of many of the effects found in previous research. However, associating a combined informant report at age 11 with an adolescent’s self-report at age 17 may have resulted in an attenuation in the magnitude of relationships compared to previous studies using single informants across time.

An additional aim of this study was to begin to understand the mechanisms by which childhood ODD is related to psychopathology in late adolescence. Results of twin analyses showed shared genetic influences contribute to the relationship between the irritable dimension and overall internalizing problems, as well as the relationship between the headstrong/hurtful dimension with AUD and CUD. Further, genetic influences on AAB and overall externalizing were shared with both ODD dimensions, and were not specific to the headstrong/hurtful dimension as was hypothesized. It should be noted that only part of the genetic variance in the ODD dimensions predicted later psychopathology, and only part of the variance in the internalizing and externalizing problems examined was predicted by the ODD dimensions. For example, 42% of variance in the irritable dimension was due to unique genetic influences separate from those shared with internalizing, and 22% of variance in internalizing was due to unique genetic influences separate from the irritable dimension. Across disorders, 5% to 17% of variance was accounted for by genetic influences shared with ODD dimensions.

It is important not to over interpret the results from behavioral genetic models. Genetic and environmental influences estimated through twin studies are specific to a particular population at a particular time (Plomin, DeFries, McClearn, & McGuffin, 2008), and heritability estimates found in a more diverse sample or more varied environment may be lower. Also, shared environmental and non-additive genetic effects cannot be modeled simultaneously due to underidentification; however, if non-additive genetic effects are present, this could inflate and bias heritability estimates. In the current study, the irritable dimension and AUD showed evidence of potential non-additive genetic effects in the twin correlations. Further, estimates of heritability should not be interpreted as fixed or determined, or to mean that environmental interventions are not possible. Finally, behavioral genetic analyses do not identify specific genes or suggest that a search for a specific gene is warranted. In fact, it is likely that each of the affective and behavioral dimensions examined in the current study are associated with thousands of gene variants which each contribute a small amount to the overall variability (Chabris, Lee, Cesarini, Benjamin & Laibson, 2015).

A few important limitations of the present study deserve consideration. First, the level of psychopathology at intake was not taken into account when examining the relationship between ODD dimensions and later psychopathology. As such, it cannot be concluded that ODD dimensions in childhood predict later disorders over and above symptoms of those disorders during childhood. In this study, the disorders examined as outcomes are only relevant for adults (e.g. adult antisocial behavior), have low variability in childhood (e.g., substance use disorders), or were not assessed at intake in at least part of the sample (internalizing disorders), and thus could not be accounted for in models. Not surprisingly, others have found weaker relationships between ODD and later psychopathology after adjusting for initial psychopathology (Lavigne et al., 2014; Stringaris & Goodman, 2009b). Second, as with many longitudinal studies, attrition occurred in the current study, resulting in decreased sample size (and power) during the follow-up assessment. While missing data were handled by using maximum likelihood estimation, missing data can result in biased parameter estimates. Third, ‘gateway’ symptoms were used in the diagnostic interviews for MDD, SOP, SPP, and PD. The ‘gateway’ items were those required for diagnosis, such as depressed mood and/or anhedonia for MDD. If the ‘gateway’ items were not endorsed, the assessment of additional symptoms was skipped, and the unassessed symptoms were assumed to be absent. Thus, it is possible that atypical or subclinical presentations were missed for those disorders by coding symptoms absent, but the approach allowed for the assessment of the most likely presentations that include the core symptoms. That said, this approach may have led to underreporting of symptoms, decreased variability, and an attenuation of observed relationships. The use of an overall internalizing symptom count helped remedy this limitation. Finally, the sample used in the current study was quite large and representative of the population of Minnesota, but was restricted in terms of diversity. The results must be replicated before they can be widely generalized.

Overall, this study supports the distinction between affective and behavioral subdimensions of ODD by providing further evidence of discriminant predictive relationships. It was shown that childhood dimensions of ODD identified risk for psychopathology experienced during late adolescence, an important developmental period. Common genetic influences contributed to these long term relationships between childhood and late adolescent mental health outcomes. Fortunately, it has been previously shown that the risk of developing secondary diagnoses decreases after remission of ODD (Nock et al., 2007). Thus, it is possible that successful treatment of ODD symptoms may reduce the risk of later internalizing and externalizing problems. This highlights the importance of early identification of behavioral risk factors and potential implications of early intervention.

Key points.

Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) symptom dimensions have been shown to be differentially related with other psychopathology.

The current study showed irritable symptoms in childhood are uniquely predictive of broad internalizing problems six years later in late adolescence; whereas, headstrong/hurtful symptoms are uniquely predictive of substance use disorder symptoms. Both irritable and headstrong/hurtful dimensions were uniquely predictive of broad externalizing problems and adult antisocial behavior.

Common genetic influences contribute to the long term relationships between childhood ODD symptoms and late adolescent mental health outcomes.

Symptoms of ODD in childhood pose a significant risk for various mental health outcomes in late adolescence, and successful treatment of ODD symptoms in childhood may reduce the risk of a broad range of later internalizing and externalizing problems.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants: DA036216, DA05147, and AA09367.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that they have no competing or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Achenbach TM. Integrative Guide for the 1991 CBCL/14–18, YSR, and TRF Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA Adult Forms and Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Aebi M, Plattner B, Metzke CW, Bessler C, Steinhausen HC. Parent- and self-reported dimensions of oppositionality in youth: construct validity, concurrent validity, and prediction of criminal outcomes in adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54:941–949. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Missing data techniques for structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:545–557. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th. Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ. The relative diagnostic utility of child and parent reports of oppositional defiant behaviors. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1996;6:253–259. [Google Scholar]

- Boylan K, Vaillancourt T, Boyle M, Szatmari P. Comorbidity of internalizing disorders in children with oppositional defiant disorder. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;16:484–494. doi: 10.1007/s00787-007-0624-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD. An affective dimension within oppositional defiant disorder symptoms among boys: personality and psychopathology outcomes into early adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53:1176–1183. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02598.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD, Hipwell AE, Loeber R. Dimensions of oppositional defiant disorder as predictors of depression and conduct disorder in preadolescent girls. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:484–492. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201005000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD, Loeber R, Lahey BB, Rathouz PJ. Developmental transitions among affective and behavioral disorders in adolescent boys. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:1200–1210. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD, Boylan K, Rowe R, Duku E, Stepp SD, Hipwell AE, Waldman ID. Identifying the irritability dimension of ODD: Application of a modified bifactor model across five large community samples of children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2014;123:841–851. doi: 10.1037/a0037898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabris CF, Lee JJ, Cesarini D, Benjamin DJ, Laibson DI. The fourth law of behavior genetics. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2015;24:304–312. doi: 10.1177/0963721415580430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Costello J, Angold A. Childhood and adolescent psychiatric disorders as predictors of young adult disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:764–772. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Augenstein TM, Wang M, Thomas SA, Drabick DAG, Burgers DE, Rabinowitz J. The validity of the multi-informant approach to assessing child and adolescent mental health. Psychological Bulletin. 2015;141:858–900. doi: 10.1037/a0038498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Applied Missing Data Analysis. New York (NY): Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ezpleleta L, Granero R, de la Osa N, Penelo E, Domenech JM. Dimensions of oppositional defiant disorder in 3-year-old preschoolers. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;53:1128–1138. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Malhotra S, Basu D. Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), the forerunner of alcohol dependence: a controlled study. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;11:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW. Missing data analysis: making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:549–567. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipwell AE, Stepp S, Feng X, Burke J, Battista DR, Loeber R, Keenan K. Impact of oppositional defiant disorder dimensions on the temporal ordering of conduct problems and depression across childhood and adolescence in girls. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52:1099–1108. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02448.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Carlson SR, Taylor J, Elkins IJ, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of substance-use disorders: findings from the Minnesota Twin Family Study. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:869–900. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, McGue M. Minnesota Twin Family Study. Twin Research. 2002;5:482–487. doi: 10.1375/136905202320906327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes MA, Malone SM, Elkins IJ, Legrand LN, McGue M, Iacono WG. The Enrichment Study of the Minnesota Twin Family Study: increasing the yield of twin families at high risk for externalizing psychopathology. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2009;12:489–501. doi: 10.1375/twin.12.5.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger FV, Polancyk GV, Goodman R, Rohde LA, Graeff-Martins AS, Salum G, Gadelha A, Pan P, Stalh D, Stringaris A. Dimensions of oppositionality in a Brazilian community sample: testing the DSM-5 proposal and etiological links. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52:389–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne JV, Gouze KR, Bryant FB, Hopkins J. Dimensions of oppositional defiant disorder in young children: heterotypic continuity with anxiety and depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2014;42:937–951. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9853-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater BJ, Homel J. Irritable and defiant sub-dimensions of ODD: their stability and prediction of internalizing symptoms and conduct problems from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2015;43:407–421. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9908-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maughan B, Rowe R, Messer J, Goodman R, Meltzer H. Conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder in a national sample: developmental epidemiology. Journal of Child Psychololgy and Psychiatry. 2004;45:609–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He J-P, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Benjet C, Georgiades K, Swendsen J. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Study-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 7th. Los Angeles (CA): Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Kazdin AE, Hiripi E, Kessler RC. Lifetime prevalence, correlates, and persistence of oppositional defiant disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:703–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, DeFries JC, McClearn GE, McGuffin P. Behavior Genetics. 5th. New York (NY): Worth Publishers; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Roberson-Nay R, Leibenluft E, Brotman MA, Myers J, Larsson H, Lichtenstein P, Kendler KS. Longitudinal stability of genetic and environmental influences on irritability: from childhood to young adulthood. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2015;172:657–664. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14040509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen HU, Helzer JE, Babor TF, Burke J, Farmer A, Jablenski A, Pickens R, Regier DA, Sartorius N, Towle LH. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview: an epidemiologic instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1988;45:1069–1077. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360017003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe R, Costello JE, Angold A, Copeland WE, Maughan B. Developmental pathways in oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:726–738. doi: 10.1037/a0020798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe R, Maughan B, Pickles A, Costello EJ, Angold A. The relationship between DSM-IV oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder: findings from the Great Smokey Mountains Study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43:365–373. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage J, Verhulst B, Copeland W, Althoff RR, Lichtenstein P, Roberson-Nay R. A genetically informed study of the longitudinal relations between irritability and anxious/depressed symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2015;54:377–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Sameroff AJ, Cicchetti D. The transition to adulthood as a critical juncture in the course of psychopathology and mental health. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:799–806. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404040015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Goodman R. Three dimensions of oppositionality in youth. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009a;50:216–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Goodman R. Longitudinal outcome of youth oppositionality: irritable, headstrong, and hurtful behaviors have distinctive predictions. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009b;48:404–412. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181984f30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Zavos H, Leibenluft E, Maughan B, Eley TC. Adolescent irritability: phenotypic associations and genetic links with depressed mood. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169:47–54. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10101549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welner Z, Reich W, Herjanic B, Jung KG, Amado H. Reliability, validity, and parent-child agreement studies of the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (DICA) Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1987;26:649–653. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198709000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan YM, Stringaris A, Maughan B, Barker ED. Developmental continuity of oppositional defiant disorder subdimensions at ages 8, 10, and 13 years and their distinct psychiatric outcomes at age 16 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52:961–969. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]